in MONTEREY COUNTY

|

||

Here in Monterey County, condors from the Sespe project began appearing by the year 2000. On 11 June 2000, nine Sespe condors settled on the roof of the Oliver observatory operated by the Monterey Institute for Research in Astronomy (MIRA) on Chews Ridge in the Santa Lucia Mountains. The MIRA caretaker, Ivan Eberle, took these impressive shots at MIRA during that event ... the avian equivalent, I suppose, of the discovery of a passing comet [photos above & right © Ivan Eberle, used with permission; all rights reserved]. After resting a bit they took off and flew south again, leaving Monterey County airspace within a few hours. Condors last nested in Monterey County in 1905. The Ventana Wilderness Sanctuary, a private non-profit group, began releasing captive-raised condors in January 1997. Condor pairs formed, found nest sites, laid eggs, and hatched wild young in Monterey County by 2006. The very first nest discovered in March 2007 featured the pairing of condors known as C208 (a female) and C192 (a male). Researcher Joseph Brandt managed this wonderful shot of C208 peering into the nest while Jospeh was checking the status of the egg (below © Joseph Brandt/VWS, used with permission). |

||

|

||

The

nest site was in the jumbled rock face of a very remote cliff in the

Ventana Wilderness (below © D. Roberson). All condors were then

wing-tagged: the male of the pair, C292, is sitting near the nest in

March 2007 (left © Joe Burnett). Because the interior of the cave

could not be viewed from any location, VWS made 3 nest entries in 2007

to confirm the presence of an egg, and (later) to check on the health

of the chick (second row below, right © Joe Burnett). Each entry

required a team with helicopter and rappelling expertise (second row

below, left © Joe Burnett). The chick eventually fledged in Sep

2007 but, alas, was killed later that year, probably by a Golden Eagle.

Two other nests that year, though, fledged young that survived. The

nest site was in the jumbled rock face of a very remote cliff in the

Ventana Wilderness (below © D. Roberson). All condors were then

wing-tagged: the male of the pair, C292, is sitting near the nest in

March 2007 (left © Joe Burnett). Because the interior of the cave

could not be viewed from any location, VWS made 3 nest entries in 2007

to confirm the presence of an egg, and (later) to check on the health

of the chick (second row below, right © Joe Burnett). Each entry

required a team with helicopter and rappelling expertise (second row

below, left © Joe Burnett). The chick eventually fledged in Sep

2007 but, alas, was killed later that year, probably by a Golden Eagle.

Two other nests that year, though, fledged young that survived. |

||

|

||

|

||

Today, wild-hatched condors are among the cohort of condors centered on the Big Sur coast and at Pinnacles National Monument. There are nesting pairs in both populations, but birds fly from the coast to the Pinnacles, or vice versa, whenever they desire. There are ranches that provide still-born calves for condors to eat, but they also feast on dead deer and other carcasses. Lead poisoning, which comes from eating animals killed by hunters with lead shot, remains one of the biggest challenges to condor survival. On the Big Sur coast, condors have learned to follow Turkey Vultures to dine on “wild” food, including sea lion or cetacean carcasses on the Big Sur coast. The foraging on dead marine mammals is particularly poignant since the California Condor was first described to science in 1792 by George Vancouver from a condor eating a dead whale on the shores of Monterey Bay. In this photo from May 2006 (below © Ryan Choi), three condors are among the other scavengers (Turkey Vultures and Western Gull) at the carcass of a Gray Whale on a remote beach on the Big Sur coast. Among the full-length articles on the recovery of California Condor on the Big Sur coast is that by Roberson (2008) in Rare Birds Yearbook 2009. A number of these photos were published with that article. |

||

|

||

|

||

At about the turn of the 21st century, the United States issued a series of quarters featuring the fifty states: the California quarter was issued in 2005. The symbols chosen to represent California on the reverse side of the coin were John Muir, Yosemite Valley, and the California Condor (inset above). Condor researcher Joe Burnett holds that California quarter (above, photo © D. Roberson) at a favored condor site on the Big Sur coast. It is an overlook along Hwy 1 high above a rocky cove used by California Sea-lion to breed or to lounge onshore. Condors search this area for stillborn seal-lions or other carcasses, and can sometimes be found sitting on the steep cliff below the overlook.

Julia Pfeiffer Burns SP is 5.1 miles south of the Big Sur Scenic Overlook, and can also be a good spot to look for condors soaring above the ridges to the east. Condors are most active on sunny days without fog, and prefer mid-day when updrafts are present. Some years ago there was a roost at Pfeiffer Big-Sur SP (which is 3 miles north of Nepenthe Restaurant), viewable from the Hwy 1 bridge over the Big Sur River (also a good spot for American Dipper). Andrew Molera SP is another 4.8 miles north of Pfeiffer Big-Sur SP, and condors sometimes fly over the ridges there, east of Hwy 1. |

||

|

||

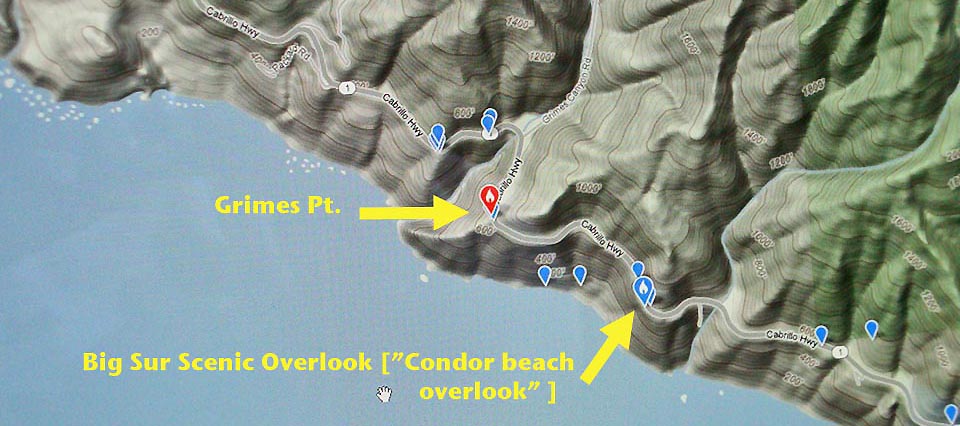

All released condors have wing tags (MTY releases have carried white, yellow, blue, or orange tags) and each has a number on the leading edge of its wing. It is difficult to determine the color of the tag -- and particularly hard to determine the number -- unless you get very good views through a telescope or you are fairly close. Even at that, you will see only two numbers, not the three numbers used for tracking. You have to know the combination of wing tag color and the two-digit number to i.d. a particular individual. Radio-tracking is the preferred method of following condor movements; each condor carries a small antennae. In short, with condor releases having occurred for 15 years and wild breeding for more than 5 years, it is not really possible to determine which condor is which particular individual, unless you are part of the condor recovery team. You can keep up on the progress of the re-introduction of condors in Monterey County at the Ventana Wilderness Society's website. Searching for MTY condors: Highway One along the entire Big Sur coast is good from the vicinity of Bixby Bridge south to Lucia. Watch for swirling groups of Turkey Vultures — sometimes condors are with them. Sometimes condors cruise the coastline alone. Beware that vultures can look "huge" when roosting close to you [if you have any doubt you are looking at a condor, you aren't]. When a dead seal or sea lion washes ashore, condors may feed on the carcass for weeks. One such event in July 2000 was on a beach visible from dirt pull-offs on Highway 1, just a half-mile north of the entrance to Julia Pfeiffer-Burns State Park (7.1 miles south of "Nepenthe" restaurant, or a half-mile south of the paved parking lot labeled "Vista Point" that has an outline of a Gray Whale painted on the pavement). More recently, condors are most often encountered at Grimes Pt. or the "Big Sur Scenic overlook" [map above]. There are times, though, when condors soar right over Highway 1. The following two photos are of yellow-tagged #22 right over our vehicle on 18 Dec 2011 (© D. Roberson). |

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

For example, yellow-tagged adult condor "04" (above) is named "Amigo," and the combination of color and number makes it #204. He is an adult male hatched in 1999 at the San Diego Zoo. After release and becoming an adult, he paired in the wild with a female named "Cosmo". But in 2010 Amigo was found badly injured and was taken back into captivity to be nursed back to health. By time time Amigo was released again, Cosmo was paired with another male. Now, in 2012, Amigo has lost his territory but has become of the foster parent to young condor "Fuego," white-tagged #70 (left), whose full number is #470. Fuego is a wild-fledged condor that survived the 2010 Basin Fire that swept over the VWS release site and came very close to Fuego's cave. When these photos were takin in Feb 2012, the two (Amigo and Fuego) were always seen together, both in flight and, when Amigo landed, so did Fuego, who then scrambled up the steep cliff to join his foster parent. At the same time, though, a third condor was watched in flight, bearing white tage "38." We ran into Tim Huntington, a local condor-watcher and wildlife photographer, who explained this condor was a visitor from the Pinnacles flock. The "Condor Spotter" website also identifies this adult female is one types in "38" and chooses "white tag." Of course, one must be able to determine both the wing tag and color to use these resources. It is also wise to keep in mind that there is interchange between the Big Sur and the Pinnacles condors, as well as visits from southern California birds. Still, it is a great time to be enjoying the California Condors in Monterey County (young Fuego, overhead, below © D. Roberson). Good luck in your search.... |

||

|

||

Literature cited:

|

The

prehistoric California Condor — one of the world's great birds — is

back in the skies of Monterey County. Prior to the recovery project,

the last wild condor in Monterey County was seen 10 Dec 1980. That was

when the entire world population, centered around Mt. Pinos in southern

California, was on the brink of extinction. Eventually all of the last

27 wild condors were captured in hopes of captive breeding, the final

one in April 1987. The captive breeding effort was successful: the

world population was over 80 birds by the time of the first releases of

captive-bred condors in January 1992 at the Sespe Condor Sanctuary,

Ventura County. By January 2000, there were 53 condors back in the wild

and another 105 in captivity.

The

prehistoric California Condor — one of the world's great birds — is

back in the skies of Monterey County. Prior to the recovery project,

the last wild condor in Monterey County was seen 10 Dec 1980. That was

when the entire world population, centered around Mt. Pinos in southern

California, was on the brink of extinction. Eventually all of the last

27 wild condors were captured in hopes of captive breeding, the final

one in April 1987. The captive breeding effort was successful: the

world population was over 80 birds by the time of the first releases of

captive-bred condors in January 1992 at the Sespe Condor Sanctuary,

Ventura County. By January 2000, there were 53 condors back in the wild

and another 105 in captivity.

A map from

A map from  The first California Condor known to science was described from the shores of Monterey Bay in 1792.

The first California Condor known to science was described from the shores of Monterey Bay in 1792.  The "countability" of MTY condors:

From a bird-lister’s standpoint, the captive-bred released birds in the

late 1990s and early 2000s were not “countable” condors. Captive-raised

birds are not "countable" under the American Birding Association (ABA)

rules, even those released back into the wild. However, this changed

with the fledging of wild young from wild nests within the Condor's

native range. Local observers long ago agreed that wild-hatched birds

would be "countable" on all lists.

The "countability" of MTY condors:

From a bird-lister’s standpoint, the captive-bred released birds in the

late 1990s and early 2000s were not “countable” condors. Captive-raised

birds are not "countable" under the American Birding Association (ABA)

rules, even those released back into the wild. However, this changed

with the fledging of wild young from wild nests within the Condor's

native range. Local observers long ago agreed that wild-hatched birds

would be "countable" on all lists.  With 'countability' issues out of the way, it is

sometimes possible to determine exactly which condor you have seen.

Condors still do have radio transmittors (see the antennae sticking out

of the back of the adult, above [25 Feb 2012 © D. Roberson]) and

still do have wing tags. With combination of tag color and number, one

can determine the three-digit condor number, and then check out

With 'countability' issues out of the way, it is

sometimes possible to determine exactly which condor you have seen.

Condors still do have radio transmittors (see the antennae sticking out

of the back of the adult, above [25 Feb 2012 © D. Roberson]) and

still do have wing tags. With combination of tag color and number, one

can determine the three-digit condor number, and then check out