2012 REPRODUCTIVE SUCCESS SURVEY

a web page by Don Roberson |

|

|||

| The rocky coastline of Monterey County is not for the timid. Waves, swells and storms batter the outer coast. Few birds are resident here, but foremost among them is Black Oystercatcher, listed as BLOY in 4-letter-code banding lingo ("BLOY" became our survey shorthand for this species). To learn more about this key local bird, the Monterey Audubon Society and California Audubon sponsored Black Oystercatcher surveys along the rocky coastline of Monterey County in 2011 and 2012. [Cal Audubon also sponsored similar surveys in other northern California counties.] In 2011, Monterey volunteers surveyed almost half of the county's rocky coastline and counted 127 birds, representing about 55 pairs, plus 18 young from perhaps 10 or so nests. This constituted about 9% of the 1346 oystercatchers found on statewide surveys in 2011. Monterey's Breeding Bird Atlas (Roberson & Tenney 1993) had estimated 77 pairs in the county; the survey of half the habitat suggested that the county might have as many as 100 breeding pairs. | |||

|

|||

In 2012, the project was a more intensive reproductive success survey, requiring volunteers to follow specific pairs and their nesting attempts over the course of a breeding season (May-August). Some 18 volunteers signed up at the organizational meeting on 19 May 2012, and 12 of them (67%) followed through on their commitment. [Of the six that dropped out, 3 became discouraged because of the difficulty in finding pairs and/or nests within their assigned territory; another found the project too time-consuming). The dozen volunteers on the 2012 project spent substantial effort watching the breeding efforts of 21 pairs of Black Oystercatcher. [We have some anecdotal data on another 7-8 pairs, see below.] Our most industrious volunteer, John G.H. Cant of Fremont, provided full data on 7 pairs along the southernmost coast of Monterey County (and arranged to use Big Creek Reserve as his base for each weekend visit). Most observers followed 1 or 2 pairs for the summer, although Gail Griffin & Brian Weed would, in tandem, follow 3 pairs at Pt. Lobos. The purposes of these surveys were to

Our results follow. |

|||

|

|||

Our 21 pairs laid eggs in 26 nests – in short, 5 of the pairs made re-nesting efforts after the loss of an initial clutch of eggs. The statistics on nesting success – with success meaning hatched at least 1 egg:

Of nests for which the number of eggs is known or can be unambiguously inferred: 5 nests had 3 eggs, 5 nests had 2 eggs, 1 nest had only 1 egg. Thus 2-3 eggs constituted the ‘standard’ nest. Of those nests that hatched eggs, the number of young ranged from 1-3 chicks. Nests with more than 1 young often lost one or more young: three nests which began with 2 young lost one before fledging age, and one nest with 3 chicks lost one before fledging age. Of a total of 21 young, only 5 lived to or near fledging age (38-40 days), and one of those disappeared before fledging was confirmed. Five pairs re-nested (24%) after loss of the initial clutch of eggs. One of the renesting attempts succeeded in fledging young; in 4 cases the pairs lost the second clutch of eggs, and in one case they hatched a young but it did not long survive. Three of the 21 pairs (14%) were observed copulating within the breeding territory after the loss of either the second clutch or the loss of young. However, it none of those cases were actual nests found after the late-season mating. |

|||

photo above © Michael Bolte [adult & chick in Santa Cruz Co., Aug 2012) photo below © D. Roberson (adults & chick in Pacific Grove on 28 Aug 2006) |

|||

|

|||

FLEDGING SUCCESS This is where the story gets grim. Of our 21 pairs, only 4 succeeded in fledging young. Three pairs fledged one young, and one pair fledged two. None of these were from a renesting effort. The statistics on fledging success were:

In addition, we have anecdotal information on 7-8 other pairs from Pebble Beach, Pt. Lobos, or Garrapata SP (let’s call it 7 more pairs; because different observers were involved, we are not sure of the overlap or not at Garrapata). Of these 7 pairs, six of them were just noted as paired up and acting territorial throughout the summer, but we have almost no information on their nesting efforts. One pair was seen with nest-building initiation (moving rocks about) but later checks of the site did not disclose that a nest was even finished (this pair is shown just below, as the presumed female checks out the nest site that was never used). As to the others they may have tried to nest and failed, or they may simply have not tried to nest (perhaps they were younger birds?). However, in one case a pair at Garrapata was seen with a fledging on 1 August (Blake Matheson), which means it did successfully nest there, but we don’t know the nest site or anything else about the effort. The confirmed breeding is excluded from our data for the detailed analysis of this project, but it is interesting that 1 of 7 other pairs fledged one young, a fledging rate of 14% (and thus quite similar to our 15% fledging success rate determined by pairs that were followed for the season). |

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

| All three breeding efforts at Pt. Lobos State Reserve succeeded in hatching 2-3 eggs, but before the young could fledge, all of them disappeared. Human disturbance is not considered a factor at any site – all on inaccessible islets or sea-cliffs – so one might guess that mammalian or avian predation of the chicks was involved. Along the south coast of Monterey, all 7 pairs followed nested on offshore islets. Two of the pairs had young in 2011 surveys. Four of the islets also had Western Gulls breeding, and in one situation a fisherman’s skiff near the rock could have been disturbing the pair (this also mentioned anecdotally at Garrapata SP). Two of the nests were lost at the egg stage, and five failed at the precocial young stage (including a re-nesting effort). Presumably predation was a factor in most (or all) of these failures, but we have no direct information. | |||

However, oystercatchers are long-lived. It takes about 5 years to reach breeding age, but after that strong pair ponds are formed. Banded adults on the Farallon Islands lived 9–15 years. This means each adult may have 4–10+ years to replace themselves for the population to remain stable. Fledging success of 15–19% should maintain a stable population — as appear to be the case here in Monterey County. It is the young chicks (like the one at left, photo'd in 2012 in Santa Cruz © Michael Bolte) that are the most vulnerable. |

|||

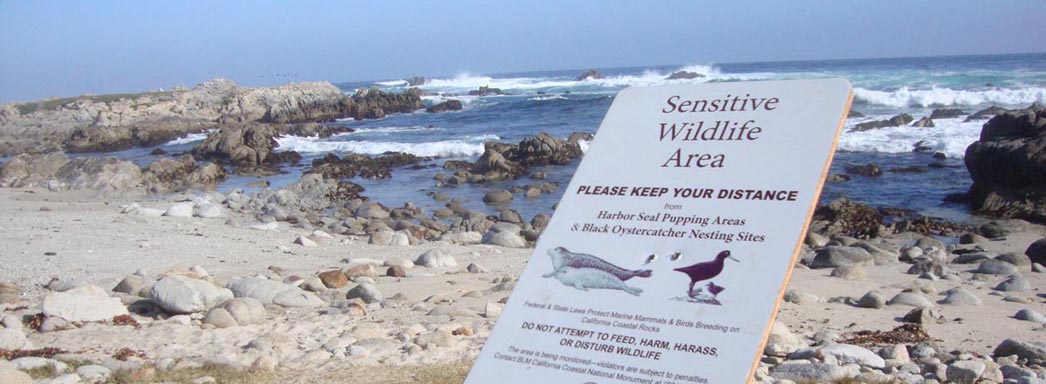

In the meantime, breeding success might be improved if vulnerable nest sites in public areas on the Monterey Peninsula could be better protected. To those ends, California Coastal National Monument (which protects the offshore rocks and islets along much of the Monterey Co. coast) has installed signs at Pt. Pinos (below) in hopes that the public can be encouraged to avoid disturbing nesting oystercatchers. |

|||

|

|||

|

|||

Photos: All photos © Don Roberson, except those attributed to Michael Bolte and Larry Rose, and used with permission; all rights reserved. Literature cited:

|

NESTING SUCCESS

NESTING SUCCESS  Of

these 4 pairs that succeeded, two were at nest sites that had young in

2011, and as we assume the same adults were involved both years, were

thus pairs that already were successfully established at an excellent

nest site. Three of the nest sites were on inaccessible islets, and the

fourth on a sea-cliff inaccessible to the public. The four fully

successful nestings were:

Of

these 4 pairs that succeeded, two were at nest sites that had young in

2011, and as we assume the same adults were involved both years, were

thus pairs that already were successfully established at an excellent

nest site. Three of the nest sites were on inaccessible islets, and the

fourth on a sea-cliff inaccessible to the public. The four fully

successful nestings were:

Our

low fledging success (only 15-19%, depending on one uses nest success

or the success of a breeding pair in a season) was unexpected for most

volunteers (and discouraging). Yet, our statistics are not unlike that

those of other studies. Hatching success across the species' range is

34-70% (Andres & Falxa 1995) — so our local hatching success of

46-57% is right in the middle of that range. Fledging success

rangewide, though, is much lower, and has been found to be only 12–39%

(Andres & Falxa 1995).

Our

low fledging success (only 15-19%, depending on one uses nest success

or the success of a breeding pair in a season) was unexpected for most

volunteers (and discouraging). Yet, our statistics are not unlike that

those of other studies. Hatching success across the species' range is

34-70% (Andres & Falxa 1995) — so our local hatching success of

46-57% is right in the middle of that range. Fledging success

rangewide, though, is much lower, and has been found to be only 12–39%

(Andres & Falxa 1995).  Our

2012 surveys add a significant amount of information to that already

known about Black Oystercatchers in Monterey County (e.g., Webster

1942, Legg 1954, Roberson & Tenney 1993). The young hatched during

a breeding season tend to remain with their parents through the fall

and early winter, but a past year's offspring is evicted from the

parental territory when courtship intensifies again in January–March

(Andres & Falxa 1995). Such young birds may then be encountered on

their own (right — presumed young oystercatcher with still much dusky

coloration on bill, photo Feb 2006 © D. Roberson) or in loose

groups foraging along the rocky shore. Paired adults, though, maintain

territories year-round and enforce them by vigorous chases.

Our

2012 surveys add a significant amount of information to that already

known about Black Oystercatchers in Monterey County (e.g., Webster

1942, Legg 1954, Roberson & Tenney 1993). The young hatched during

a breeding season tend to remain with their parents through the fall

and early winter, but a past year's offspring is evicted from the

parental territory when courtship intensifies again in January–March

(Andres & Falxa 1995). Such young birds may then be encountered on

their own (right — presumed young oystercatcher with still much dusky

coloration on bill, photo Feb 2006 © D. Roberson) or in loose

groups foraging along the rocky shore. Paired adults, though, maintain

territories year-round and enforce them by vigorous chases.