a web page by Don Roberson |

|

26 Feb 2012 Coyote Hills, ALA © Tom Grey |

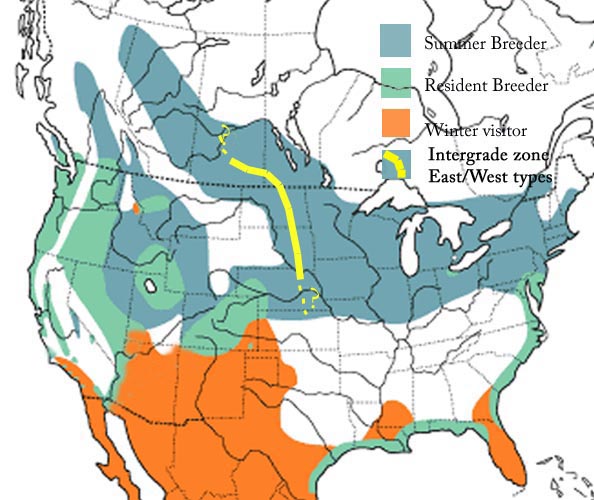

Recent research into vocalizations (Kroodsma & Verner 1987, 1997, Kroodsma 1989) has shown that Marsh Wrens can be divided into two large evolutionary types, a "western" type and an "eastern" type. These meet in a broad intergrade zone (100 miles wide or so) from at least south-central Saskatchewan to northeast Nebraska, shown roughly by the yellow line on the map (right.) The two types appear to nest assortatively as one crosses this zone, but genetically about 40% of adults in the zone show mixed ancestry. The two types might represent two biological species, or these populations may be in the process of becoming species (more research is needed). These facts draw our interest as field birders, as we begin to wonder how different populations might be identified in the field. Here in coastal central California, we know from specimens that migrants from other populations have been collected in migration and winter. This project is an effort to introduce the topic from a local perspective. It has already captured the attention of birders in Colorado, for example, who might look for both forms within that State (see Leukering & Pieplow 2010). |

||||

|

||||

| There is one additional separating point between Eastern and Western forms: Eastern birds have a complete molt after nesting (in late summer/early spring) but also most seem to have a pre-alternate body molt in spring. In contrast, Western birds have a complete molt only once a year (after nesting; late summer/early fall) and apparently do not have a spring molt of any kind; Kroodsma & Verner (1997). This means Western birds would continue to become increasingly worn and faded through breeding season — and that may account for just how faded some Western birds in July can appear. Pyle (1997) mentioned additional eccentric molt involving replacement of upperwing coverts between western and southern populations, and more eastern populations. This does not yet appear to be fully sorted out. | ||||

| Although vocally there are two (2) "evolutionary groups" of Marsh Wrens, visually there are three (3) Groups of subspecies. Pyle (1997) summarized these Groups as (a) Coastal Pacific Group — medium in size, dark rufous-brown, (b) Interior Western Group — large, pale brownish with a rufous tinge, and (c) Eastern Group — small, dull brown tinged rufous. Pyle outlined 13 subspecies to be assigned within the three Groups (plus another race in Mexico), but Kroodsma & Verner (1997) rearranged the subspecies and their assignments. They also have 13 subspecies (plus one more in Mexico) but they merged one of Pyle's races, added a new subspecies from coastal southern California (clarkae, based on Unitt et al. 1996), and readjusted boundaries. Today we might think of them as the Pacific, Interior West, and Eastern Groups. The generalized breeding range of each Group is shown below. Pacific birds and coastal Eastern populations are mostly resident, but large numbers of Interior West and the interior Eastern birds migrate south in winter. | ||||

|

||||

|

||||

| The trio of songsters above illustrate examples of the three Groups on the breeding grounds. They are not posted at the same proportional size — the Interior West birds are largest. Also, they were not photographed at exactly the same time of year (although all are spring/summer birds), but perhaps one can gain a generalized feeling about (to use Pyle's headings) the "dark rufous-brown" Pacific bird, compared to the "pale brownish" Interior West bird, next to the "dull brown tinged rufous" Eastern bird. Or not. What I see is that the "large pale brown" Interior West bird is the most different — being plain and lacking much contrast — while the Pacific and the Eastern individuals are more similar to each other — being rufous (especially on rump) and 'contrasty' and with a more prominent supercilium that contrasts with a darker crown. Indeed, the Eastern bird looks essentially "black-capped" in this shot — sometimes said to be a point to notice — but, as we shall see, that is variable in both the Pacific and Eastern populations. | ||||

| A problem in comparing Marsh Wrens is that the state of molt and wear affects color and contrast perceptions. The panel below is of four birds of the widespread California subspecies aestuarinus, but in different months. The first bird (top left below) is in fresh plumage — note the primaries are black with tiny white tips — and the plumage is fresh, with well-defined black back patch with white streaks; crisply patterned tertials; and brown overall with rusty shoulders, scapulars and rump [I don't have a month for this photo, but it most be soon after the complete molt in late summer/early fall]. The next individual (top right below) is from mid-December. It is still rather crisp and colorful, with rufous shoulders, scaps and rump; tertials somewhat less crisply patterned; and a well-defined white throat, but note that the primaries are wearing to brown and have lost their white tips. The bottom two photos are of birds in March/April. The primaries are more worn and dull brown. The rufous shoulder, scaps and rump are duller, and the overall underpart pattern is less contrasty and dull. | ||||

|

||||

| Another problem arises in juvenal plumage, which is held only briefly in summer (May-Aug, depending on location), but birds in juvenal plumage can disperse away from the breeding grounds. The top two photos in the panel below illustrate juvenal plumage, but this time in one of the Interior West races, pulverius. The bird in juvenal plumage (below, at top left in that set) is still on the breeding site but, compared to adults, is plain and dingy, without a full supercilium and with a dull darkish crown. Pyle (1997) says that juvenal-plumaged Marsh Wren "has a relatively dark crown, less distinct or no white streaking on the back, a less distinct supercilium, and loosely textured undertail coverts." Most of these points are apparent on the netted individual shown top right (below). This bird has a much darker crown than adults, almost entirely lacks the white-streaked black triangle on the back, and has a very short post-ocular supercilium | ||||

|

||||

| Contrast the juvenal-plumaged pulverius Marsh Wrens (top row above) with full adult pulverius Marsh Wrens (bottom row above) from April and July. Adults of Interior West populations have a mostly brown crown, a less well-defined supercilium that those in the Pacific or Eastern Groups, and are overall pale tan in color. There is, though, a rufous wash to the rump that can be seen on the April bird (left) with is lost by July (right). | ||||

| With these overall concepts in mind — (a) there is a distinctive juvenal plumage that needs to be considered in summer birds, and (b) that wear can significantly affect colors and patterns — we can turn to a look at photos from different populations in hopes of extracting something useful. This is on the next page in this set. | ||||

Photos: All photos © Don Roberson, except those attributed to © Mark Eaton, Tom Grey, W. Ed Harper, Sacha Heath, Greg W. Lasley, Tony Leukering, Dennis Paulson, Netta Smith, Ryan Schain, Dan Singer, and Brian Sullivan, used with permission; all rights reserved. Dan Singer also provided useful editing comments. Literature cited:

|

Marsh Wren Cistothorus paludicus

is a common but local resident in Monterey County, and that generalized

description applies to much of North America. Marsh Wrens breed in

cattail or bulrush marshes across the northern U.S. and southern

Canada, and coastal marshes on both the Pacific and Atlantic coasts.

There is a complex pattern of local resident populations and migrant

populations, as shown on this map (right) from Kroodsma & Verner

(1997). Marsh Wrens winter in the southern U.S. and n. Mexico in many

locations where they do not breed, but these still tend to be marshes

or brushy wetlands.

Marsh Wren Cistothorus paludicus

is a common but local resident in Monterey County, and that generalized

description applies to much of North America. Marsh Wrens breed in

cattail or bulrush marshes across the northern U.S. and southern

Canada, and coastal marshes on both the Pacific and Atlantic coasts.

There is a complex pattern of local resident populations and migrant

populations, as shown on this map (right) from Kroodsma & Verner

(1997). Marsh Wrens winter in the southern U.S. and n. Mexico in many

locations where they do not breed, but these still tend to be marshes

or brushy wetlands.