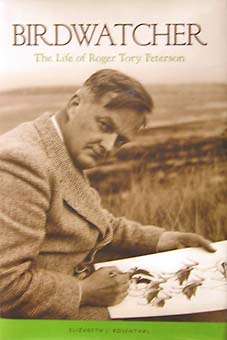

Elizabeth J. Rosenthal (2008)

a review by Don Roberson |

|

|

That was the punch line of a joke I gave to warm-up a birding crowd not long after the 1988 election. Everyone laughed. Everyone recognized the parody of Lloyd Bentsen's repartee with Dan Quayle in the vice presidential debate. And everyone immediately recognized the equivalency, in their respective realm, between Roger Tory Peterson and John F. Kennedy. That was 20 years ago. I wonder how the joke would play today. Only the older half of the birding audience would recognize the 1988 debate parody, and maybe I'd need to add a "you betcha" and a wink to tighten the vice-presidential context? And what percentage of today's audience would recognize the name Roger Tory Peterson? |

|

One can acknowledge the debt all birders owe to RTP without considering him a deity. Others may have informally bestowed on him the title "the Great Man," but my take was more modest. I am an avid reader of U.S. presidential and Civil War biographies. To me, a whiff of hagiography is the death knell to a decent read. Some Civil War biographers of T. J. "Stonewall" Jackson or Robert E. Lee just cannot free themselves from concept that their subject was a "Great Man." The best biographies of both are those that recognize the deep flaws in each man — as a person and as a general — and more accurately place the subject among his contemporaries. I had not read any prior RTP biography, and admit to having been worried about this one upon its initial receipt. I flipped through the nice selection of photos in the center until unnerved by the last shot. The photo, by Susan Drennan and taken in Roger's later years, was simply labeled "the Great Man." Ohhh-boy, I thought, not a good sign. But I need not have worried. The biography is straightforward and fair. The whole Roger is here, warts and all. I was able to spend a long weekend birding with Roger in 1983 — just him and me — and got to know him pretty well. Roger also came along on a record-setting airplane Big Day that I organized in 1982. In the 1990s, my wife Rita and I spent a day showing Roger and Ginny around the Monterey Aquarium. So I spent enough time with Roger to get a sense of his personality, and Elizabeth Rosenthal has hit it spot-on. It is the real Roger that appears in this book. Perhaps this is because the book relies heavily on interviews with those who knew him, from the beginning of his birding career to the icon he became, and all the interviewees seemed to have known the same RTP that I knew: a sharp birder, modest but competitive, generous with his time and knowledge but careless about the details of life, opinionated but willing to listen to another view, disorganized but intensely focused on the things he thought were important. And those things were birding and bird photography. By the time I knew him, painting field guides "was a slavery" (to use Greg Lasley's quote from the book, but Roger said the same to me) and Roger much preferred to do "painterly paintings," big canvas art designed to sell for high prices. The book cites Roger's high appreciation for the art of Robert Bateman, and this, too, was something that Roger had expressed to me. The first half of the book is organized more or less chronologically, from childhood until his third marriage, and hits all the high points and major stories of Roger's life. I very much like the stories — from the "dovekie" that was a practical joke designed to (and did) take Roger down a notch or two, to his close friendship with James Fisher, with whom he co-wrote Wild America, to his status as a "ladies' man" in early trip leading. There is plenty of information about the three wives; the author appears to prefer his second wife (Barbara). The second half of the book ventures away from chronology into topics of interest, such as Roger's influence on a series of environmental issues of global importance in the 1950s through 1970s, and Roger's influence on various birders, ornithologists, and artists that followed. The book then curves back to the concluding decade of Roger's life. The writing throughout is entertaining and carries the story along, and the numerous quotes from interviews or from the holiday letter that Barbara wrote each Christmas season — all set out in distinctive typeface — enlighten many of the pages. The book's weakest point is chapter 18 "Territory under Challenge," within Part Six of the saga, entitled "Bird Man of Bird Men." These pages cover Roger's relationship with the wider birding fraternity during the 1970s and 1980s, at a time when Roger updated both his Eastern and Western field guides but was faced with competition from new guides. The reviews of Roger's revised Eastern guide in 1980 were mixed: reviewers without a background in modern birder techniques loved the revision, but almost universally the top-tier birders thought it to be very disappointing. The negative reviews from the top American birders really bothered Roger. Although Roger said he kept up on the literature, he appears to have just dabbled at best. Jon Dunn's review of Roger's 1980 guide (in The Auk) called Roger's painting of "confusing fall warblers" to be among the "worst plates in the book." [Rosenthal contrasts this with a review from The Conservationist that called that plate "exceptionally well done." ] Roger responds to his critics by stating that "there are always Young Turks out there ready to climb on my shoulders, but I can only hope that they do so wearing felt slippers and not with hobnailed boots." The author doesn't have a clue who to believe in this dispute. She doesn't seem to know that it will be Jon Dunn, for example, who will write the definitive i.d. book on warblers (with Kimball Garrett, and, ironically enough, published in the Peterson field guide series in 1997). Jon was exactly right to criticize the 1980 Eastern guide for Roger's failure to keep up with current i.d. advances, and his failure to consult then-current birding experts. Roger had brought this problem on himself. He intended "to make the new Eastern guide the most critically accurate and effective field guide yet produced on any region in the world," to quote from an excerpt of a letter he wrote in 1980, and yet it wasn't even close. Roger's world of extensive travel and lecturing, art shows and publishing, painting and making money had led him far from those pushing the "frontiers of bird identification," to use the title of a book published in England in 1980. But Roger took the criticism seriously, and in the early 1980s spent a lot of time contacting local birding experts (including several of us in California) to help him with his planned update of the Western guide (published in 1990). I recall preparing some comments on plate 1 — the loons — and pointing out that the distinctive neck patterns between Common and Pacific Loons was were missed in his 1980 painting, among other points. It was true enough that his guides are primarily intended for beginners, but the 1980 book was not even remotely close to "critically accurate." I just picked it up right now (while writing this review) and find that the gulls, for just one example, are almost unrecognizable, and many are aged incorrectly. Roger’s guide is the source for numerous claims of "second winter" Glaucous that are actually first-cycle birds — his guide bungles both ages badly. The fact is that by the 1980s, Roger was no longer "the birdman among bird men." The birding world had passed him right by; he was struggling to catch up. I have eight typed letters that Roger wrote me in the 1980s, and many are on the topic of his updated guide and the competition. In January 1982 he wrote me this: "You suggest that either this year or next I should take a look at some of the Empids when they go through California during spring migration (or is it fall) so that I might evaluate behavioral characteristics that some of the experts go by. When I have mentioned some of these points to Tom Howell and one or two other academics I find that they are not fully convinced and feel that more collecting is necessary . . . Inasmuch as I will have only two double spreads to cover the western Empids I can hardly go into as much extended detail in two pages as you were able to develop in five pages [of Rare Birds of the West Coast]." Tom Howell is not a field birder up to par with folks like McCaskie, Lehman, Dunn, Garrett, Bevier, Morlan, Erickson, and many others in the 1980s. Roger was just talking to the wrong people. |

|

Yet he was quite aware of the competition. "Have you had a chance to assess the new field guides — the National Geographic book, the 3-volume Master Guide, and the update of the Robbins-Singer guide?", he wrote me in January 1984. Roger was keen to get back on top. The biography does capture Roger's intensity on this. By 1984, Roger was 76 years old, and sensitive to growing older. The book captures this aspect also. In July 1984, Roger wrote me to tell me about another Big Day effort he'd done in Texas (which fell short of our own record the previous year), and said this: "My own ears are my best asset; my eyes are giving me problems and it was partly because of my ears that our group in New Jersey broke the records for that state with 201 in the competitive Birdathon initiated by Pete Dunne." In the biography, Pete Dunne tells how Roger was the one to hear the singing Mourning Warbler from a fast-moving car during the New Jersey competition. I, too, was impressed with Roger's hearing ability during our 1983 Big Day. Late in the book, Greg Lasley tells how even Roger's acute hearing was failing. The book well captures the public's response to Roger in the latter half of his life, when he was a major celebrity in the general birding world. In the 1984 New Jersey birdathon, for example, "the main concern was keeping fans from Roger," writes the author. It was Roger's celebrity that propelled interest in the 1983 Big Day we did in California. We had a chartered airplane, and then Discover magazine, Sports Illustrated, and the Los Angeles Times each chartered other planes to follow us around California, with National Public Radio sending a team to meet us for the last few hours around Monterey. "Keeping the fans away from Roger" at Morongo Valley was a big concern of ours as well — we could only hear birds if everyone was quiet! For all that celebrity, Roger was humble and non-assuming. There is a great little story, late in the book, about Roger showing up to surprise Rich Stallcup's birding class. Roger actually did the same once for me, when I was teaching an adult education bird class at night in my home. One evening Roger was there when the students arrived, and they found a slim, older gentlemen sitting on the couch. Their delight when it turned out to be Roger T. Peterson was memorable. Roger took part in all the discussions — we were looking at slides of cormorants that session — and then spun a few stories for all. Fortunately, a lot of those stories are in this biography. The book captures the man quite well, and is a great read throughout. I am pleased to recommend it highly. |

|

|

|

More details are on a web site about this book. |

|

Photos: 4 May 1983 at north end, Salton Sea, California © Don Roberson |

Probably

most, maybe all. But today's young birders do not grow up memorizing

their Peterson field guide, as all of us who were birding in 1988 would

have done. Today's crop of birders prefer the Sibley guide or the Nat'l

Geo. Yet they all should know, acknowledge, and appreciate that it was

RTP (as many of us tended to call him from afar) that made it all

happen. This lively biography is an excellent way to get to know him.

Probably

most, maybe all. But today's young birders do not grow up memorizing

their Peterson field guide, as all of us who were birding in 1988 would

have done. Today's crop of birders prefer the Sibley guide or the Nat'l

Geo. Yet they all should know, acknowledge, and appreciate that it was

RTP (as many of us tended to call him from afar) that made it all

happen. This lively biography is an excellent way to get to know him. Roger

actually did come out to California to spend a weekend with me and look

at migrant Empids at Morongo Valley. That was the first weekend of May

1983. As it turned out, a Spotted Redshank had just shown up at the

Salton Sea, and we ended up spending all our time there, looking for

the rarity. We didn't refind the bird until the third day. Roger never

complained about the change in plans. Indeed, he was having so much fun

photographing breeding-plumaged Red Knots and other waders that he

never mentioned the fact we failed to look at Empids! It was typical

Roger — he was happier taking photos than "working" on the field guide.

Roger

actually did come out to California to spend a weekend with me and look

at migrant Empids at Morongo Valley. That was the first weekend of May

1983. As it turned out, a Spotted Redshank had just shown up at the

Salton Sea, and we ended up spending all our time there, looking for

the rarity. We didn't refind the bird until the third day. Roger never

complained about the change in plans. Indeed, he was having so much fun

photographing breeding-plumaged Red Knots and other waders that he

never mentioned the fact we failed to look at Empids! It was typical

Roger — he was happier taking photos than "working" on the field guide.