a web page by Don Roberson |

|

HAWAIIAN HONEYCREEPERS Drepanidini a traditional bird family but now a lineage embedded within the Fringillidae |

|||

|

|||

Loss and extinction of Hawaiian honeycreepers has continued. Although new methods have "split" some taxa into multiple species — the list of known species back 200 years is now 39 species (several recent splits occurred in just 2015, per AOU Check-list) — only 17 are known to currently be extant. Since Austin's book, eight more additional Hawaiian honeycreepers have gone extinct, including Kauai 'Akialoa Hemignathus stejnegeri (not seen since 1969), 'O'u Psittirostra psittacea (lost about 1987), and Po'o-uli Melamprosops phaeosoma (the last one died in captivity in Nov 2004; see Powell 2008). Only 17 honeycreepers remain alive today — or just 43% of species that are know from the last 200 years — and about half of them are in decline. There are multiple causes, including loss of habitat, avian malaria carried by mosquitoes that have reached the top of all island except Maui and Hawaii, introduced pigs and other exotics, hurricanes, and genetic bottlenecks. The remote cloud forest in which rare drepanids still exist are beautiful but forbidding places, such as Waikamoi Preserve on the slopes of Haleakala, Maui (below), access is by permit only with approved guides. |

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

We've had the good fortune to visit the highlands of the Big Island of Hawaii with Jack Jeffrey, the premier photographer of the Hawaiian honeycreepers (right, a 1989 photo of him showing us a flowering 'ohi'a tree). Jeffrey's research on the 'Akiapola'au (below) revealed multiple strategies. 'Akiapola'au uses its heavy, straight lower mandible to hammer holes in dead wood invested with beetle larvae, and then uses its longer, hooked upper mandible to extract the grub. Another strategy is to drill a deep hole into the cambium layer of an 'ohi'a tree, much as sapsuckers (a woodpecker in the New World) do. Each 'well' drilled produces a few drops of sap and attracts insects. The 'Akiapola'au, like sapsuckers, feeds on both the sap and the insects when it revisits the 'wells' later. |

|||

|

|||

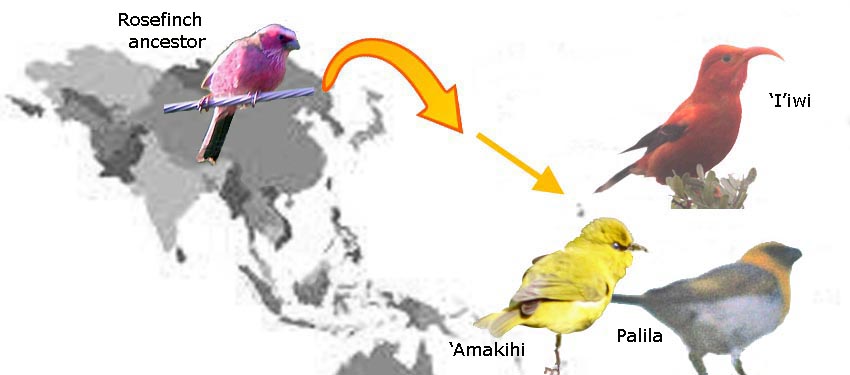

| It was long a mystery how any landbirds could have reached Hawaii, out in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. The islands themselves are volcanic and did not emerge from the sea until 5.7 million years ago (mya), when Kauai and Nihau formed. It was about then that the islands were colonized by ancestors of today's Hawaiian honeyeaters. Before the most recent genetic evidence, it had been hypothesized that Hawaiian honeycreepers reached Hawaii from the New World. Initial theories revolved around ancient nectar-feeders, like Bananaquit, but osteological studies did not support that theory, and by the turn of the new century Pratt (2005) wrote that "the close relationship of Hawaiian honeycreepers and cardueline finches can no longer be reasonably questioned." Pratt (2010) hypothesized that a siskin, or Pine Grosbeak, or even a crossbill could be the ancestral colonizer. | |||

|

|||

Based on genetic studies, it is now known that all the Hawaiian honeycreepers emerged from just that single colonization of Eurasian rosefinches (Carpodacus), presumably from Asia (Lerner et al. 2009, Zuccon et al. 2012). All the major lineages — the nectar feeders (like 'I'iwi), the 'warbler-like' predators (like 'Amakihi), and the seed-eaters (including today's Palila on Hawaii) — had diverged after Oahu emerged (4.0–3.7 mya) but before the formation of Maui and adjacent islands (2.4–1.9 mya; Lerner et al. 2009). This is illustrated above, using some of my photos. Having evolved just 5 mya, Hawaiian honeycreepers are much too young a lineage to be consider a "Family" among the many ancient lineages that are currently supportable at that status. Almost all of today's bird Families diverged 20 mya or more. The traditional "family" Drepanididae was down-graded to a subfamily [Drepanidinae] but the early 21st century (e.g., Pratt 2005). However, the Handbook of the Birds of the World series — whose format is planned years in advance — did permit Pratt (2010) to write and illustrate an entire account of the Hawaiian Honeycreepers as if it were a full bird Family. With the most recent genetics (Lerner et al. 2009, Zuccon et al. 2012) might be better reduced to a "tribe" [Drepanidini]. I list it that way in the title (above), but the AOU does not formally designate the honeycreepers as a tribe. Currently (2015) the AOU simply lists the genera among this radiation as members of a much broader Carduelinae subfamily, along with rosefinches, Purple & House finches, crossbills, siskins, and goldfinches. |

|||

The various types of Hawaiian honeycreepers evolved in a "single line" evolution — as is usual in isolated radiations — with one exception. The emergence of the "creepers" is an example of convergent evolution. The "creepers" are the Hawaii Creeper (right) on the Big Island, 'Akikiki (or 'Kauai Creeper') Oreomystis bairdi, and Maui Alauahio (or "Maui Creeper") Paroreomyza montana. These arose through two separate divergences from the main evolutionary line near the base of the lineage, and then they evolved to resemble each other in their barking-hunting habits through convergent evolution; Reding et al. (2009), Lerner et al. (2011). The species that are doing the best in lowland forests — and are thus the ones must likely to be seen by tourists — are a contrast in red and green. The bright red male 'Apapane (below left) is the most widespread species, occurring on all the major islands (Hawaii, Maui, Oahu, Kauai) plus Lanai and Molokai. It has an amazing vocal range and is the 'symphony' of native birdsong in good habitat. The widespread native green bird is the traditional 'Amakihi — which is now split into three species: Hawaii 'Amakihi [below right — on Hawaii (this photo) and on Maui], and then two single-island endemics, Kauai 'Amakihi Chlorodrepanis stejnegeri and Oahu 'Amakihi Chlorodrepanis flava. Like 'Apapane, the Hawaii 'Amakihi frequents a wide range of elevations, from lowland forest to cloud forest. |

|||

|

|||

The threats to the survival of Hawaiian honeycreepers are many. Those endemic to Kauai have collapsed as exotic mosquitoes reached the top of the island, bringing avian malaria and other diseases to the entire island population. Exotics such as pigs create wallows in which mosquitoes thrive. Non-native ungulates eat favored plants. An introduced snake (like the Brown Tree Snake that wiped out the avifauna of Guam) could be deadly. Hurricanes could devastate protected areas — all these threats discussed in detail in Pratt (2005). The scarcity and specialization of some species can lead to genetic bottlenecks or worse. The Po'o-uli on Maui might have been the most specialized of all honeycreepers — specializing on native land snails in rain forest — and its recent extinction may well be linked to the introduction of non-native garlic snails that replaced native snails in prime areas, leaving the bird without adequate prey. Hawaii (and Guam) may seem like paradise to tourists, but it is surely "Paradise Lost" from an avian perspective. Doug Pratt wrote (2005) that in his lifetime he had "seen the Alaka'i [swamp on Kauai] go from a dawn greeted exuberantly by songs of 'O'o'a'a, Kama'o, Puaiohi, Kauai 'Elepaio, 'O'u, 'Akeke'e, 'Akikiki, Kauai 'Amakihi, 'Anianiau, 'I'iwi and 'Apapane to mornings nearly silent except for the alien voices of shama, Hwamei, and bush-warbler in just [25 years]. With a little bit of luck and few strategic research breakthroughs, most of the remaining honeycreepers can probably hang on for decades. But if any one of the potential disasters [discussed in his book] were to render today's high elevation refugia inoperative, we can bid them all of wistful 'aloha'." |

|||

Photos: Michael Walther photographed Maui Parrotbill Pseudonestor xanthophrys in Waikamoi Preserve, Maui, on 8 June 2008. The uppermost photo of 'I'iwi Vestiaria coccinea, 'Akiapola'au Hemignathus wilsoni, Hawaii Creeper Loxops mana, and Hawaii Akepa Loxops coccineus were taken on 2 Jan 2012 in Hakalau Forest NWR on the slopes of Mauna Kea, Hawaii; the photo of Jack Jeffrey was taken there in August 1989. Photos of Palila Loxioides bailleui and Hawaii 'Amakihi Chlorodrepanis virens were taken high on the slopes of Mauna Loa, Hawaii, in Aug 1989 and Jan 2012, respectively. The 'Akohekohe Palmeria dolei, the young 'I'iwi, and the habitat shot were taken at Waikamoi Preserve, on the slopes of Haleakala, Maui, in March 2015. Photos © Michael Walther, as credited and used with permission, and © Don Roberson; all rights reserved. Bibliographic note:

Literature cited:

|

Until

scientists developed molecular techniques to study genetic evolution,

there were just theories about how the Hawaiian honeycreepers came to

the Hawaiian islands and evolved into one of the most spectacular

radiations of birds in the world. Most everyone agreed they were so

unique that they warranted their own family, the Drepanididae [an

example was the relatively common 'I'iwi, above].

Drepanids were in the colorful big book that I enjoyed as a child

(Austin 1961), which surveyed the 155 bird families then recognized. It

explained that they probably arrived 5 million years ago and "prospered

and diversified so rapidly that it hardly seems possible for such

variation to have developed from a single ancestral type in so short a

time)." Even then the book said that 9 of the 22 known species was

already extinct, and "another 8 or 10 survive precariously in small,

local populations." One of those is the remarkable Maui Parrotbill (left, in a equally remarkable photo by Michael Walther); only about 500 remain.

Until

scientists developed molecular techniques to study genetic evolution,

there were just theories about how the Hawaiian honeycreepers came to

the Hawaiian islands and evolved into one of the most spectacular

radiations of birds in the world. Most everyone agreed they were so

unique that they warranted their own family, the Drepanididae [an

example was the relatively common 'I'iwi, above].

Drepanids were in the colorful big book that I enjoyed as a child

(Austin 1961), which surveyed the 155 bird families then recognized. It

explained that they probably arrived 5 million years ago and "prospered

and diversified so rapidly that it hardly seems possible for such

variation to have developed from a single ancestral type in so short a

time)." Even then the book said that 9 of the 22 known species was

already extinct, and "another 8 or 10 survive precariously in small,

local populations." One of those is the remarkable Maui Parrotbill (left, in a equally remarkable photo by Michael Walther); only about 500 remain.

One learns interesting things when spending quality time in prime habitat. For example, young 'I'iwi

are orange-headed and pale-bellied, but the scarlet that will cover its

body starts to appear in the lesser wing coverts (above).

One learns interesting things when spending quality time in prime habitat. For example, young 'I'iwi

are orange-headed and pale-bellied, but the scarlet that will cover its

body starts to appear in the lesser wing coverts (above).

I

have enjoyed efforts over 3 decades to search for most of the

still-living Hawaiian honeycreepers. I'm now missing only the two

northwest island species [Laysan Finch Telespiza cantans and Nihoa Finch T. ultima — these may resemble the original Carpodacus-like

ancestor most closely] and the 'Akikiki on Kauai. But it is very sad to

realize that a half-dozen have become extinct in my lifetime and that

others, like Hawaii 'Akepa (male right, taking

flight;), continue to decline. The 'Akepa is now restricted to small

areas of protected forest high on Mauna Kea, Hawaii.

I

have enjoyed efforts over 3 decades to search for most of the

still-living Hawaiian honeycreepers. I'm now missing only the two

northwest island species [Laysan Finch Telespiza cantans and Nihoa Finch T. ultima — these may resemble the original Carpodacus-like

ancestor most closely] and the 'Akikiki on Kauai. But it is very sad to

realize that a half-dozen have become extinct in my lifetime and that

others, like Hawaii 'Akepa (male right, taking

flight;), continue to decline. The 'Akepa is now restricted to small

areas of protected forest high on Mauna Kea, Hawaii.