a web page by Don Roberson |

FURNARIDS Furnariidae |

||||||

|

||||||

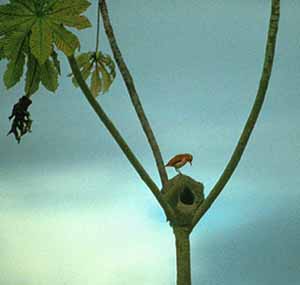

Little is known about Lesser Hornero of the Amazon basin. This nest was in the crotch of a bare Cecropia tree emerging from flood water along the Napo River in Peru. The nest is the typical hard-mud nest of horneros, but is apparently undescribed (see Remsen 2003).

|

||||||

Furnarids are even a larger family now than when I first posted a Furnariidae page in 1999. There were 235 species in the family. Splits and a few new species have added species, but what has changed must dramatically, enlarging the family by more than 20%, is what groups are included within the Furnariidae. Traditionally the Ovenbirds [Furnariidae] were considered a separate family from the Woodcreepers [Dendrocolaptidae]. This standard approach was carried over into the Handbook of the Birds of the World project; Remsen (2003) and Marantz et al. (2003). Yet as early as Feduccia (1973) it was proposed that the woodcreepers were embedded within the Furnariidae, thus making that family paraphyletic. Genetic data (Chesser 2004, Fjeldså et al. 2005, Irestedt et al. 2006, 2009, Moyle et al. 2009) strongly support this position, with the genera Geositta [miners] and Sclerurus [leaftossers] being basal to all other ovenbirds plus woodcreepers. Sibley & Ahlquist (1990) merged woodcreepers into the Furnariidae, and both the AOU and SACC have since followed suit. However, an alternative classification would be to recognize all three major groups as families, i.e., Scleruridae, Furnariidae, and Dendrocolaptidae (see Moyle et al. 2009).

The open question is where the genus Xenops belongs. Xenops acts like a nuthatch, foraging on trunks and branches, often in mixed-species flocks. An example is Plain Xenops (right), a species that ranges from southern Mexico to Argentina Whether the three species of "true" xenops [Slender-billed X. tenuirostris, Plain X. minutus, Streaked X. rutilans] are more closely related to ovenbirds or to woodcreepers is uncertain (see Fjeldså et al. 2005, Irestedt et al. 2009, Moyle et al. 2009), and some (e.g. John Boyd) suggest they form a fourth subfamily Xenopinae. |

||||||

More than 30 furnarids are called foliage-gleaners. There are many in the Amazon Basin forests, more in the montane Andean cloud forests, some in jungles of Central American, and some that are endemic to specific wooded habitats. Here are three examples from the humid forests of southeast Brazil: White-collared Foliage-Gleaner (right), an aggressive species the dominates mixed species flocks; White-eyed Foliage-gleaner (below left), a more sedate species at mid-levels, and Buff-fronted Foliage-gleaner (below right), a canopy specialist with an odd distribution that includes Panama and the Andes as well as southeast Brazil. |

||||||

|

||||||

The furnarids mentioned so far are important components of huge undergrowth, sub-canopy, or canopy flocks in Amazonian or montane rainforests. Many other furnarid species are adapted to open arid habitats, from the thrasher-like earthcreepers of the southern Andes to high-altitude canasteros than run between clumps to alpine vegetation. And then there are the spinetails, many of which live in pairs or family groups in dense thickets or cane. Like most furnarids, they are best found by their vocalizations — and can be teased into the open through tape playback — but are otherwise very secretive. |

||||||

|

||||||

I still vividly recall struggling up steep slopes on Abra Malaga in the Peruvian Andes, where one must stop every few yards to breathe and pray that one can avoid altitude sickness for just a little while longer, to reach isolated patches of Polylepis woods near 14,000' elevation to locate the endangered White-browed Tit-Spinetail Leptasthenura xenothorax; Parker & O'Neill (1980) have a description of this area and its little known birds. |

||||||

Remsen (2003) discusses the amazing variety in nests among the Furnariidae, noting that the "family name does at least draw particular attention to nest shape, which is highly appropriate for a family known for its distinctive and often absurdly large nests." Thornbirds in the genus Phacellodomus and cachalotes in the genus Pseudoseisura are known for massive nests; the Firewood-gatherer Anumbius annumbi exemplifies its English name. Pairs gather thornscrub to weave into complex globular nests. And yet there are still furnarids yet unmentioned. The genus Cinclodes has over a dozen species ranging through all elevational habitats in the Andes. While Bar-winged Cinclodes C. fuscus hunts on the ground near tree-line, hopping along small rivulets at 11,000' elevation, and the Royal Cinclodes C. aricomae is an endangered endemic of paramo in southeast Peru and western Bolivia, other cinclodes live at sea level. The Peruvian Seaside Cinclodes (below) is shaped and colored rather like a drab starling but acts like a rocky shorebird as it forages among mussels exposed by low tide. |

||||||

|

||||||

| For foregoing overview has left out Point-tailed Palmcreeper Berlepschia rikeri, which acrobatically gleans items from the blades and undersides of palm branches and leaflets. There are a chilia and a rayadito in Chile, and another rayadito is an endemic to the Juan Fernandez Islands. There are enigmatic softails along the major rivers of northern South America, and another has just been discovered there. There are likely other species yet to be discovered. | ||||||

Photos: The frog-catching Rufous Hornero Furnarius rufus was in the Brazilian Pantanal on 19 July 2010. The Lesser Hornero Furnarius minor at the nest was just off Llachapa I. next to Sucasari camp, near the confluence of the Napo and Amazon rivers, Peru, in June 1987. Bob Tintle and I were in the same canoe and snapped almost identical photos, but he had a better lens so I use his shot. The Plain Xenops Xenops minutus was on the Osa Peninsula, Costa Rica, on 27 Dec 2007. The White-collared Foliage-gleaner Anabazenops fuscus was at Itatiaia NP, Brazil, on 6 Aug 2010. The White-eyed Foliage-gleaner Automolus leucophthalmus and the Buff-fronted Foliage-gleaner Philydor rufus were both at Intervales State Park, Brazil, on 31 July 2010. The Sharp-billed Treehunter Heliobletus contaminatus was at Itatiaia NP, Brazil, on 5 Aug 2010. The Pallid Spinetail Cranioleuca pallida was at Itatiaia NP, Brazil, on 4 Aug 2010. The Cinereous-breasted Spinetail Synallaxis hypospodia was at a wooded thicket in the Brazilian Pantanal on 23 July 2010. The party of Rusty-backed Spinetail Cranioleuca vulpina were along the Rio Claro, Mato Grosso, Brazil, on 19 July 2010. The Yellow-chinned Spinetail Certhiaxis cinnamomea and the family of White-lored Spinetail Synallaxis albilora were in Pantanal marshes, Brazil, on 20 July 2010. The Araucaria Tit-Spinetail Leptasthenura setaria and the Itatiaia Thistletail Oreophylax moreirae were both at high elevations in Itatiaia NP, Brazil, on 5 Aug 2010. The Peruvian Seaside Cinclodes Cinclodes taczanowskii was on the Islas Ballestras off Paracas, Peru, in June 1987; this photo was from a boat. Photo © Don Roberson, except one attributed to Bob Tintle, used with permission; all rights reserved. Bibliographic note: Family Book:

Now, of course, the lengthy family text, species accounts, and wonderful photos in the Handbook of the Birds of the World project serve as a fine introduction. Ovenbirds plus Miners are in Remsen (2003); Woodcreepers in Marantz et al. (2003). Literature cited:

|

The

fact that miners and leaftossers are "basal" to the rest of the family

means that their ancestors evolved earliest into a separate lineage,

making them more distinctly different than woodcreepers are to the rest

of the ovenbirds. Since woodcreepers are so distinctive and easily

recognized, and have been thought of as a family for so long, it is now

convenient to think of the Furnarids as three subfamilies. I approach

them that way here, setting up three separate pages to break-up this

huge family. It also makes it easy to elevate these groups to family

level if that approach were to be preferred:

The

fact that miners and leaftossers are "basal" to the rest of the family

means that their ancestors evolved earliest into a separate lineage,

making them more distinctly different than woodcreepers are to the rest

of the ovenbirds. Since woodcreepers are so distinctive and easily

recognized, and have been thought of as a family for so long, it is now

convenient to think of the Furnarids as three subfamilies. I approach

them that way here, setting up three separate pages to break-up this

huge family. It also makes it easy to elevate these groups to family

level if that approach were to be preferred: In

South America, furnarids occur from sea-level to tree-line. One large

group is the foliage-gleaners which are "drab, mainly brown birds that

inhabit the darkened interior of rainforests and cloudforests" of the

New World (Parker 1979). Ted Parker wrote this fantastic introductory

article on a group of difficult foreign genera with particular

relevance to Amazonian Peru — it's a shame there aren't more papers

like it. I pull it out to study it before every South American trip.

Unfortunately, it is difficult to find since Continental Birdlife only lasted a couple a years as a journal.

In

South America, furnarids occur from sea-level to tree-line. One large

group is the foliage-gleaners which are "drab, mainly brown birds that

inhabit the darkened interior of rainforests and cloudforests" of the

New World (Parker 1979). Ted Parker wrote this fantastic introductory

article on a group of difficult foreign genera with particular

relevance to Amazonian Peru — it's a shame there aren't more papers

like it. I pull it out to study it before every South American trip.

Unfortunately, it is difficult to find since Continental Birdlife only lasted a couple a years as a journal.

Often

in flocks with foliage-gleaners are other localized furnarids called

treehunters, treerunners, woodhaunters, hookbills, barbtails, or

tuftedcheeks. There are even two recurvebills in specialized bamboo

habitat. Each furnarid has a specific niche. Sharp-billed Treehunter

(right) of southeast Brazil works through dense growths of bromeliads

in the canopy. The more widespread Sharp-tailed Streamcreeper Lochmias naematura hunts along the edges of streams and ponds inside the forest. Most of these birds are quite hard to see, let alone photograph.

Often

in flocks with foliage-gleaners are other localized furnarids called

treehunters, treerunners, woodhaunters, hookbills, barbtails, or

tuftedcheeks. There are even two recurvebills in specialized bamboo

habitat. Each furnarid has a specific niche. Sharp-billed Treehunter

(right) of southeast Brazil works through dense growths of bromeliads

in the canopy. The more widespread Sharp-tailed Streamcreeper Lochmias naematura hunts along the edges of streams and ponds inside the forest. Most of these birds are quite hard to see, let alone photograph.

At high elevation there are various tit-spinetails, thistletails, and wiretails. In southeast Brazil, two such specialties are Araucaria Tit-Spinetail (far left; on an Araucaria tree) and Itatiaia Thristletail

(near left). The latter is confined to the highest mountains of

southeast Brazil, a distribution unlike any other Brazilian endemic.

At high elevation there are various tit-spinetails, thistletails, and wiretails. In southeast Brazil, two such specialties are Araucaria Tit-Spinetail (far left; on an Araucaria tree) and Itatiaia Thristletail

(near left). The latter is confined to the highest mountains of

southeast Brazil, a distribution unlike any other Brazilian endemic.