TROPICBIRDS Phaethontidae

-

Species in family 3

-

Species observed [DR] 3 (100%)

-

Species photo'd [DR] 3

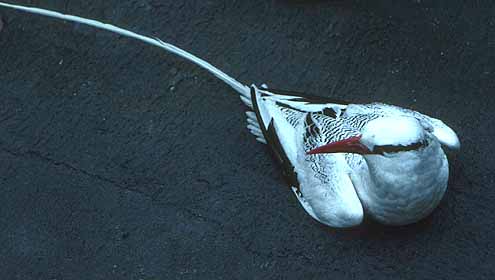

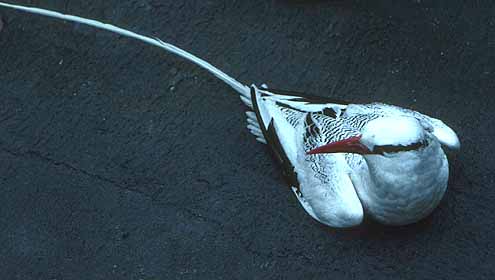

The Tropicbirds are graceful tropical seabirds, cruising the open ocean

for fish. Lovely long-tailed adults, like this White-tailed Tropicbird

(left), come ashore on remote islands to nest. Younger birds, with decidedly

shorter tail streamers like the Red-tailed Tropicbird (below), spend

all their time at sea. Because birds in immature plumages are never seen

from shore, they remain very little known. Far offshore, however, Red-tailed

Tropicbird is the common species in the eastern tropical Pacific. These

birds do not yet have red tails; instead the short tail streamers are white

(as on this bird) or barely pinkish.

The Tropicbirds are graceful tropical seabirds, cruising the open ocean

for fish. Lovely long-tailed adults, like this White-tailed Tropicbird

(left), come ashore on remote islands to nest. Younger birds, with decidedly

shorter tail streamers like the Red-tailed Tropicbird (below), spend

all their time at sea. Because birds in immature plumages are never seen

from shore, they remain very little known. Far offshore, however, Red-tailed

Tropicbird is the common species in the eastern tropical Pacific. These

birds do not yet have red tails; instead the short tail streamers are white

(as on this bird) or barely pinkish.

This young Red-tailed (right) is in molt. You can see that the two

outer primaries are old and retained; the inner primaries have been renewed

but the third-from-outer is still growing in and is thus shorter than the

outer two. Note that the tips of the new feathers are smooth and rounded

while the old outers are more pointed and ragged. We know so little about

these pelagic birds that molt sequences are not fully understood. Note

also the webbed feet -- these are truly oceanic birds.

Tropicbirds nest in small, loose colonies on oceanic islands. These

locales must be either predator free, as is Cousin Island in the Seychelles

where this White-tailed Tropicbird (below) has its nest on the forest

floor up against the base of a large tree, or they use inaccessible ledges

or caves on canyon walls (as on Kauai, Hawaiian Islands). Adult pairs perform

spectacular display flights over their breeding islands, and the fuzzy

down-covered baby chicks (peeking out from its parent, below) are about

as cute as birds can get.

There are only three species of tropicbirds. The White-tailed Tropicbird

has the widest range as it is found in tropical oceans around the world.

There is even a race (P. l. fulva) on Christmas Island in the Indian

Ocean whose plumage is tinged golden apricot (colloquially called the "Golden

Bosunbird"). Despite the wide range, however, this species tends to stay

closer to shore while the Red-tailed Tropicbird is a pelagic specialist,

occurring hundreds of miles offshore. Red-tailed is very widespread in

the Pacific & Indian Oceans, but it is absent from the Atlantic. The

third species is the Red-billed Tropicbird (two photos below). Like

the White-tailed, it tends to be an inshore species. Its range is restricted

to the western Pacific (esp. west Mexico & the Galapagos), the tropical

Atlantic, and the Red Sea area of the northwestern Indian Ocean.

All tropicbirds specialize of tropical fish, and for all flying fish

are often the most important parts of their diet. All have black feathering

just in front of the eye which presumably makes it easier to observe flying

fish against the glare of the open ocean. Red-tailed -- with bigger bills

-- take even the larger flyingfish such as those in the genus Cypselurus.

All species will eat squid or crustaceans when available.

It is always striking to see a long-tailed adult tropicbird sitting

on the sparkling blue ocean -- with its tail raised to form a graceful

arch -- as is the Red-billed below (top photo). Occasionally a tropicbird

will "crash" into a ship, as did the Red-billed (bottom photo) that

I photographed aboard the McArthur during four months at sea in

1989 on a NOAA tuna-purpose research cruise. It may have been disoriented

by our lights at night which attracted both the tropicbird and lots of

squid. We released it unharmed.

Despite their striking tails and colorful bills, and despite their names,

neither the tail nor the bill color is very important in tropicbird identification.

All three species have occurred in California, and hurricanes have transported

tropicbirds well inland on both coasts. Few assumptions should be made

when one is lucky enough to encounter a tropicbird. I have created a page

on this identification topic, so if you're interested, click on:

TROPICBIRD

IDENTIFICATION PAGE

All three tropicbirds are closely related within the single genus Phaethon;

there is a fossil from England aged at 50 million years ago that corresponds

to a fourth (now extinct) species (Orta 1992).

Photos: Both the in-flight and nesting White-tailed

Tropicbird P. lepturus photos were taken on Cousin I., Seychelles,

in Nov 1992. The young Red-tailed Tropicbird

P.

rubricauda was taken in the eastern tropical Pacific at about 14°N,

145°30'W. The Red-billed Tropicbird

P.

aethereus sitting on the ocean was just off San Clemente I., s. California,

on 12 Sep 1982; the adult Red-billed came aboard the McArthur just south

of the Galapagos Is. on 26 Sep 1989. All photos © D.

Roberson; all rights reserved.

Bibliographic note:

There is no "family book" per se of which I'm aware (there are numerous

coffee-table "survey" books that include tropicbirds among other sea-birds),

but an excellent introduction to the family, with striking photos, is in

Orta (1992). That survey, however, has overlooked the eastern tropical

Pacific distribution of Red-tailed Tropicbird (correctly shown in Pitman

1986). Because it is so pelagic, Red-tailed appears to be the least known

but a good summary of what was known at that time is in Gould et al. (1974).

Literature cited:

Gould, P. J., W. B. King, and G. A. Sanger. 1974. "Red-tailed

Tropicbird" in Pelagic Studies of Seabirds in the Central and Eastern

Pacific Ocean. Smithsonian Contrib. Zool. 158.

Orta, J. 1992. Family Phaethontidae (Tropicbirds) in del Hoyo, J., Elliott,

A., & Sargatal, J., eds. Handbook of the Birds of the World.

Vol. 1. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Pitman, R. L. 1986. Atlas of Seabird Distribution and Relative Abundance

in the Eastern Tropical Pacific. NOAA, Nat. Mar. Fish. Serv., Southwest

Fisheries Center admin. rpt. LJ-86-02C.

TOP

BACK TO HOME PAGE

BACK TO LIST OF

BIRD FAMILIES OF THE WORLD

Page created 20-21 Jan 2000

The Tropicbirds are graceful tropical seabirds, cruising the open ocean

for fish. Lovely long-tailed adults, like this White-tailed Tropicbird

(left), come ashore on remote islands to nest. Younger birds, with decidedly

shorter tail streamers like the Red-tailed Tropicbird (below), spend

all their time at sea. Because birds in immature plumages are never seen

from shore, they remain very little known. Far offshore, however, Red-tailed

Tropicbird is the common species in the eastern tropical Pacific. These

birds do not yet have red tails; instead the short tail streamers are white

(as on this bird) or barely pinkish.

The Tropicbirds are graceful tropical seabirds, cruising the open ocean

for fish. Lovely long-tailed adults, like this White-tailed Tropicbird

(left), come ashore on remote islands to nest. Younger birds, with decidedly

shorter tail streamers like the Red-tailed Tropicbird (below), spend

all their time at sea. Because birds in immature plumages are never seen

from shore, they remain very little known. Far offshore, however, Red-tailed

Tropicbird is the common species in the eastern tropical Pacific. These

birds do not yet have red tails; instead the short tail streamers are white

(as on this bird) or barely pinkish.