|

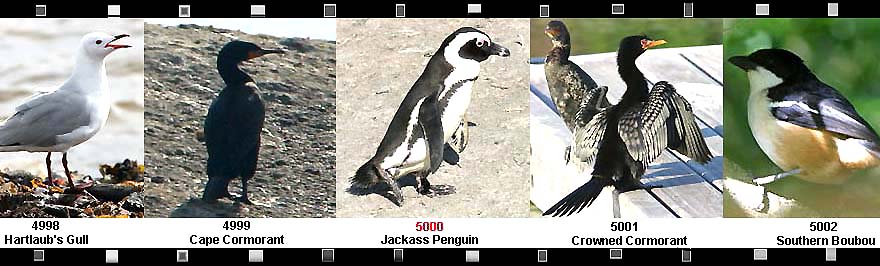

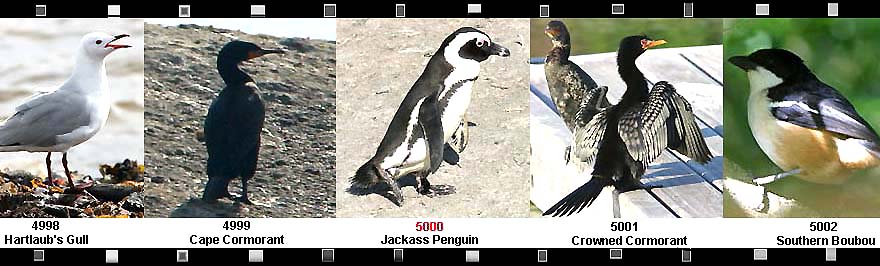

In any event, a short slice of my mind's-eye newsreel from this past summer is posted above. It is the slice that includes my 5000th world bird, plus those just before and just after the milestone. Fortunately, I do have photos of all of them in this slice of the movie. Seeing 5000 birds in the world had long been a personal goal, as it was the number I had chosen as roughly equivalent to "half of the birds of the world." I'll never see all 10,000 birds in the world — indeed, no one ever will — but "seeing half" has long been a difficult but not unreasonable goal. When I started seriously birding in the early 1970s, the world list was thought to be about 8,000 birds. I still vividly recall Arnold Small's article about seeing his 4000th lifer — which was thought to approximately half the world's birds back then — a White-headed Piping-Guan in Surinam [article originally appeared in the Los Angeles Audubon Society newsletter Western Tanager (May 1976) and was reprinted in Birding 8: 145-148 (1976)]. It is true that dozens of new species have been discovered since then, but the change from 8000 birds to 10,000 birds in the world largely reflects new views on taxonomy, and much new information about vocalizations, habitats, and even DNA, that allows scientists to apply the biological species concept more accurately. Before Rita and I left for our southern Africa trip in late June 2005, my 'life list' stood at 4997 species. It had been stuck there since the previous summer's visit to northern China, at least as the taxonomy stood at that time. Our Rockjumper guide, Richard White, picked us up at the Cape Town airport in the morning of 30 June, and I asked him to be very careful about where we went first. I wanted something 'special' for #5000. It was impossible to avoid seeing Hartlaub's Gull (#4998) and Cape Cormorant (#4999) as we drove to Simonstown, south of Cape Town. Richard says he usually birds his way into the penguin colony at Boulders Bay but this time we did it in reverse. We hustled down the path, looking neither left nor right, bought our tickets, and took a step out onto the boardwalk. And there was bird #5000: Jackass Penguin! One kick-ass bird in its own right. Indeed, there is an entire breeding colony here. Rita took this pic of me with #5000 (below) |

|

||

| The

Jackass

Penguin Spheniscus demersus, sometimes called "African

Penguin" or "Black-flippered Penguin", is endemic to the rocky coasts of

southwestern Africa. Its preferred name (e.g., the one used in Dickinson

2003) refers to from its loud, braying donkey-like call. It is one of four

species in the genus: the others are Magellanic

S. magellanicus

of southern South America, Humboldt S. humboldti of the west coast

of South America, and Galapagos S. mendiculus of the Galapagos Islands.

I'd only seen two other species of penguin prior to this trip, but one

of them was Humboldt Penguin, so this was not a new genus for me. It was,

however, Rita's first penguin — a life family for her!

All of the Spheniscus penguins have similar black-and-white patterns. Jackass Penguin is most similar to Magellanic — they both occur on the southern tips of continents — and they both have a bright pink eyering and loral patch formed by bare skin [Humboldt does as well but also has much pink on the base of the bill]. Jackass typically has a single breastband (like the one shown to the right), while Magellanic typically has two breast bands, but there is overlap because some Jackass Penguins also carry a double band. Magellanic and Humboldt have heavier bills than Jackass; the small Galapagos Penguin has a much slimmer bill (from Martinez 1992). There were once colonies of millions of Jackass Penguins (see stories in Peterson 1979). Today, Birdlife International (2000) lists it as Vulnerable, with an estimated world population of 180,000 birds and declining. Just seven islands support 80% of the breeding population. It is threatened by disturbance and predators (e.g., feral cats) at some colonies, by ocean pollution and oil spills (a recent spill affected 40% of the population and became a major rescue effort), but mostly by food shortages attributable to large fish catches by commercial purse-seine fisheries. These penguins feed heavily on sardines and anchovies and squid, and may forage up to 40 km offshore (Birdlife International 2000, Martinez 1992). During our visit to South Africa, we saw a few penguins elsewhere along the rocky coast, and at the Cape Gannet gannetry at Lamberts Bay, to the northwest of Cape Town. The range extends north well into Namibia. |

||

|

||

| The colony at Boulders Bay in Simonstown is a relatively new phenomena. Two pairs wandered ashore in 1982 and began breeding. The boulders on the beach here are said to be 540 million years old. The beach is in a residential community but the locals decided that if the penguins were going to take over a prized local beach, they might as well be protected and managed. Boardwalks now give visitors access to the colony, which has grown to up to 3000 in recent years. The adults molt in December out at sea, but return in January and nest from February-August (Anon. 2003). | ||

According

to the brochure we received on entry (Anon. 2003), the colony has grown

recently because of regulations that have reduced trawling in False Bay,

and thus increasing the penguins' prey base. The adults are apparently

monogamous and mate for life. Other stats given are these: the penguins

swim at an average speed of 7 km/hr., and they can stay submerged for up

to two minutes. According

to the brochure we received on entry (Anon. 2003), the colony has grown

recently because of regulations that have reduced trawling in False Bay,

and thus increasing the penguins' prey base. The adults are apparently

monogamous and mate for life. Other stats given are these: the penguins

swim at an average speed of 7 km/hr., and they can stay submerged for up

to two minutes.

During our visit on 30 June, the colony was declining in size. There were still some full-grown by downy youngsters about (left), many of them in patchy molt from brown down to gray juvenal feathers. There were, however, a couple of very late nests with still quite small young. Rita was filming one of those nests when disturbed (below left); that nest is shown in close-up (below right). |

||

|

||

| This is the penguin kept most commonly in zoos and aquariums around

the world. In California there are exhibits of these penguins at Cal Academy

in San Francisco, the Monterey Bay Aquarium in Monterey, and at several

zoos or commercial establishments in southern California. One was even

"seen in the wild" near Chimney Rock, Pt. Reyes, Marin Co., from 3-16 Feb

1981 (Binford 1985), a clear escapee from captivity. The penguins at the

San Francisco Aquarium made headlines last year by embarking on a multi-month

'migration' in their exhibit pen, swimming frantically around and around

until, one day, they stopped. Birds do undertake some seasonal movements

in the wild, especially those movements associated with molt.

All in all, a great bird to tic for # 5000.

|

||

|

||

|

|

PHOTOS: All photos on this page are © 2005 Don Roberson; all rights reserved.

Literature cited:

Anonymous. 2003. "Welcome to Boulders" brochure. Table Mountain National Park, South African National Parks, Cape Town.TOPBinford, L.C. 1985. Seventh report of the California Bird Records Committee. Western Birds 16: 29-48.

Birdlife International. 2000. Threatened Birds of the World. Barcelona & Cambridge, U.K., Lynx Edicions & Birdlife International.

Dickinson, E., ed. 2003. The Howard & Moore Complete Checklist of the Birds of the World. 3d ed. Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, N.J.

Martinez, I. 1992. Family Spheniscidae (Penguins) in del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., & Sargatal, J., eds. Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 1. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Peterson, R.T. 1979. Penguins. Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

GO TO LIST OF BIRD FAMILIES OF THE WORLD