|

photo'd at

|

|

photo'd at

|

Another of Stuart's articles had an even more profound impact on my life. In 1974, just as I was nearing the end of college, he published "Birding Planet Earth — A World Overview" (Birding 6:203-216). Back then Stuart Keith had seen more birds in the world than anyone else, and his breezy paper literally danced with the joy of world travel searching for the beautiful, the unique, the elusive, the rarest of the rare. "One thing we can say for sure," he wrote, is that no one would ever "get them all." One might have a goal to search out half the birds of the world — this was cited as the goal of Roger Tory Peterson, and Stuart himself, and became my goal as well in due course— but there were just too many impossibly difficult species for anyone to see them all. But it was the effort to do so — the process and the joy of ticking them off one by one — that energized those like Stuart who took up the quest. I began my quest with a trip to Colombia the very next year.

As he wrote back in 1972, Stuart was "an avid birder since the age of

15, when I was given my first pair of binoculars. ... I have now had 14

years' exposure to professional ornithologists, and I have a very good

idea of how their minds work and what kinds of things they are doing. At

the same time, I have lost none of my original enthusiasm for the listing

game, as those who have birded with me well know. The sight of my first

Gray-crested Helmet-shrike on the Serengeti Plains of Tanzania in December

(my last new one) gave me just as great a thrill as the sight of my first

Fieldfare in an English field 25 years ago."

This

excitement for the next new bird never waned. Last summer he told me of

his upcoming trip to Micronesia with Sally, other members of his family,

and Doug Pratt, the world expert on Micronesian birds. I reminded Stuart

of my own brief visit to Truk (now called Chuuk) back in 1978, when I had

photographed the Caroline Islands Ground-Dove Gallicolumba kubaryi

(left; taken on Moen I. in 1978), a species that Stuart still needed. I

was able to boast that Doug Pratt had borrowed my photo for use in painting

his field guide to Micronesia. This

excitement for the next new bird never waned. Last summer he told me of

his upcoming trip to Micronesia with Sally, other members of his family,

and Doug Pratt, the world expert on Micronesian birds. I reminded Stuart

of my own brief visit to Truk (now called Chuuk) back in 1978, when I had

photographed the Caroline Islands Ground-Dove Gallicolumba kubaryi

(left; taken on Moen I. in 1978), a species that Stuart still needed. I

was able to boast that Doug Pratt had borrowed my photo for use in painting

his field guide to Micronesia.

In February 2003, Stuart and friends finally reached Chuuk. I'll let Sallyann Keith pick up the story: "We were met at the airport in Chuuk by Mary Rose Nakayama, a beautiful 25-year-old woman who has a project to educate her island people concerning the Oceanic Flycatcher and nature conservation in general... When Doug asked her if she knew where to find the Caroline Island Ground Dove she said 'It's in my back yard!' That evening we saw the Oceanic Flycatcher, endemic to Chuuk, sitting on a nest on the grounds of the lovely Blue Lagoon Hotel. The next morning Mary Rose led us up a hill behind her house where, sure enough, the Ground-Dove came out on a branch and preened for us all! Doug and Stuart gave each other the high five! It was the last life bird Stuart was to see, spectacular and exciting." |

I always feared Stuart would go too soon. He had quadruple bypass heart

operation in 1991, angioplasty in 1993, carotid artery surgery in 1999,

and a heart valve replacement in 2001. Nevertheless, as Sally wrote: "he

went on extended birding trips to Kenya (1988) New Zealand (1990) Costa

Rica (1993) Ghana (1997) Namibia and South Africa (1999) Morocco and Spain

(2002) and Micronesia, his final birding tour. He always said he wanted

to die on a birding trip, on a mountain top, seeing a new life bird. He

got his wish. He died peacefully on the tropical island of Chuuk within

hours of snorkeling in the Blue Lagoon" and seeing the Caroline Ground-Dove.

I don't know what his world list was exactly, but about 6600, or approximately

two-thirds of the birds on this globe. He was way over "half" and enjoying

every minute of it.

There

is a line in Stuart's 1974 "Birding Planet Earth" article that has resonated

with me for decades. Stuart wrote, addressing himself to the American Birding

Association readers who mostly looked at North American birds — the ABA

listers: "Tough birds like Yellow Rail, Boreal Owl, and Ross's Gull are

a snap compared to elusive myths like the Congo Peacock, the Long-tailed

Ground-Roller of Madagascar and the Great Argus Pheasant of southeast Asia."

For no other reason than those three species being Stuart's prime examples

of the near mythical and the elusive, they became among my "most wanted

birds" in the world. What a glorious day it was to finally see a Great

Argus Pheasant in the thick lowland jungles of Borneo in 1988, even if

she was a female! Even more impressive was the Long-tailed Ground-Roller

in southwest Madagascar (right; taken in Nov 1992). But as to Congo Pheasant,

well, that one will elude me. That is a bird of deep, dark central Africa.

Stuart's country... There

is a line in Stuart's 1974 "Birding Planet Earth" article that has resonated

with me for decades. Stuart wrote, addressing himself to the American Birding

Association readers who mostly looked at North American birds — the ABA

listers: "Tough birds like Yellow Rail, Boreal Owl, and Ross's Gull are

a snap compared to elusive myths like the Congo Peacock, the Long-tailed

Ground-Roller of Madagascar and the Great Argus Pheasant of southeast Asia."

For no other reason than those three species being Stuart's prime examples

of the near mythical and the elusive, they became among my "most wanted

birds" in the world. What a glorious day it was to finally see a Great

Argus Pheasant in the thick lowland jungles of Borneo in 1988, even if

she was a female! Even more impressive was the Long-tailed Ground-Roller

in southwest Madagascar (right; taken in Nov 1992). But as to Congo Pheasant,

well, that one will elude me. That is a bird of deep, dark central Africa.

Stuart's country... |

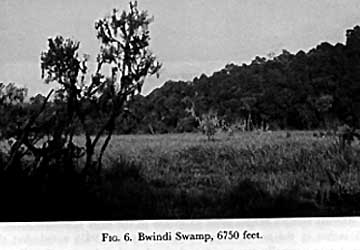

I didn't fully realize until recently just how much field research Stuart had done in Africa. Yes, I knew how he liked to brag that he was the only person in the world to see every species of Sarothrura rail. Known as "flufftails," each of the 9 species is virtually impossible to spot in wet dense thickets or rank murky swamps. To see one is a real treat (I have seen just one), but all nine is, well, close to impossible. But Stuart's field work came to me most directly this past year while planning a trip to Uganda, including a visit to the Impenetrable Forest. It was then that I came upon a 1969 paper entitled The Avifauna of the Impenetrable Forest, Uganda. The lead author was, of course, Stuart Keith. There he and colleagues had set up field camps at various elevations in the early 1960s, collecting and mist-netting and tape-recording birds. The paper analyzed bird distribution by elevation, some of it incredibly steep. "The Impenetrable Forest is well named," he wrote, drifting into the third person tense: "For example, when Keith put up his nets at Ruhiza, he had to cut footholds into the steep earth to keep himself from slipping." He visited Bwindi (Mubwindi) Swamp which "Friedmann's collectors were the first to discover, and it yielded such rarities as Bradypterus graueri" (Grauer's Brush Warbler). The photo of that swamp, published by Keith et al. in 1969 (below left) shows an enchanted and yet nearly-forbidden place, much as it is today (below right). And it still takes an incredibly steep hike to reach it!

|

|

| This call, which has been likened to the noise produced by a tuning fork, was for a long time regarded superstitiously by the local Africans. It has been ascribed to various sources: some thought is was made by a Banshee, others ascribed it to a snake, a skink, a land snail, or a small mammal. Perhaps the most prevalent theory was that it was the wail of agony made by a chameleon giving birth. Now we know that it is made by nothing more dangerous than a diminutive forest-dwelling rail. |

Which brings me to Stuart's sense of humor... dry and very British,

perfect for the occasion. Read his gentle jibes at those still thinking

of Africa as the "great unknown" (despite the volumes of Birds of Africa!)

in his letter to the editor in 2002 (Birding 34:264-266), or see

his reviews of three new African books (Birding 35:86-90. "It may

be a personal quirk," he wrote, "but I am always bothered by birds perched

on thin air, without any kind of substrate" in field guides. He complains

that "there's not much joy in the Joyful Greenbul" painting in one guide,

but then hastens to praise a text (Bull. African Bird Club 1:32-38)

that gets the greenbuls right.

Given the depth of his wit and perspective, correspondence with him

was a treat. In January 2001, I wrote Stuart to congratulate him upon the

publication of Vol. 6 of BOA. Knowing my interest in bird families, Stuart

wrote back, and then told the story of his most recent birding trip:

One just has to laugh at such stories. Like his good friend the late Arnold Small, Stuart was a great swapper of grumbling tales of birds seen and missed, enjoyed and endured. He was the perfect antidote to the heavy-handed seriousness in some of today's top birders who seem always gloomy -- whereas Arnold and Stuart were always having fun. |

|

In recent years, Rita and I got to visit with Stuart and Sally perhaps

once a year, either at their Redding home or at ours in Pacific Grove.

From time to time I'd try to get Stuart to talk about this or that taxonomic

decision other minutiae published in the most recent volume of BoA, but

he would demur. "That was last year," he'd say, "lets talk about what is

yet to come!" The little collage above is representative: I picture Stuart

and Sally as the ostriches wandering up an African road, in good fellowship

and looking forward, always, with me, playing the role of the grumpy ground-hornbill,

left behind to look back and nit-pick this or that. What an inspiration

he was! What a great joy to have known such a man! He cannot be replaced;

he can now only be remembered.