The American Birding Association's [ABA] Rules Committee devised a fine

scheme that divided the World into nine non-overlapping Regions for purposes

of bird listing around the World. This was a concept created and promoted

by the Rules Committee chairman at the time, Bob Pyle, and in the end some

excellent decisions about the dividing lines were made and published (I

was a member of the Committee at the time of these deliberations). Yet,

for purposes of showing photos of different areas of the World, I find

that I prefer to consider them from a somewhat different perspective. I,

too, have nine "Realms" but they are defined a bit more along biogeographic

grounds and serve better the purposes I have here. These are (click

on the link to bring up a separate page for each Realm):

Without getting into detailed definitions, but to outline the areas covered,

suffice it to say that I start with the ABA definitions but make these

modifications:

-

I split Eurasia avifaunally -- giving separate identities to Asia and to

the Western Palearctic -- but use the ABA's definition for distinguishing

between Asia and Australasia (the line is between Sulawesi and Halmahera)

-

I include North Africa, Europe, and the Middle East in a Western Palearctic

Realm that mirrors the boundaries of the Handbook of the Birds of the

Western Palearctic series

-

The African Realm is restricted to sub-Saharan Africa

-

North America is separated from South America more biogeographically, with

Central America considered part of the Neotropical Realm. The dividing

line is ill-defined but is somewhere in the northern part of Mexico. Like

the ABA, I include the Caribbean in North America (= the Nearctic Realm).

-

I combine the three oceanic Regions (Pacific, Indian, Atlantic) into one

Oceanic Realm

-

The Oceanic Realm include all pelagic waters beyond the continental shelves

(so that I include some of my California albatrosses and petrels as in

the Oceanic Realm, although they are "countable" on ABA lists, state lists,

county lists, and the like because they were within 200 nautical miles

of the continent). All tiny uninhabited islands that serve solely or primarily

as seabird colonies are also included in this grouping.

-

The Oceanic Island Realm is composed of the larger, forested, inhabited

islands that have landbirds and which geographically in the ABA's three

oceanic Regions, including Madagascar, New Zealand, New Caledonia, the

Galapagos, Hawaii, and all the Pacific islands

-

The Antarctic Realm is just the continent of Antarctica and the major adjacent

islands with penguin colonies. Since I've not been here yet, this page

will have to feature a guest photographer.

This is simple enough in practice, and the result is not far distant from

the faunal map I studied as a youngster (in Austin's Birds of the World

1961; reproduced here). My major differences from the old Birds of the

World map is assigning eastern Russia & China to the Asian Realm;

included New Zealand among the Oceanic Islands instead of Australasia but

assigned Halmahera and the Moluccas to Australasia (thus the Birds of Paradise

are an endemic family to Australasia, as they should be -- a position also

adopted unanimously by the ABA Rules Committee), and I push the Neotropics

a bit farther north in Mexico (thus all the furnarids and wood-creepers

are Neotropical endemics) while retaining the Caribbean in the Nearctic.

But these are mere quibbles in the grand scheme of things. Thinking of

the World as divided between my nine distinctive "realms" gives me a sense

of order that is comforting. [Of course, in the "real" world -- including

evolution -- is anything but orderly.]

This is simple enough in practice, and the result is not far distant from

the faunal map I studied as a youngster (in Austin's Birds of the World

1961; reproduced here). My major differences from the old Birds of the

World map is assigning eastern Russia & China to the Asian Realm;

included New Zealand among the Oceanic Islands instead of Australasia but

assigned Halmahera and the Moluccas to Australasia (thus the Birds of Paradise

are an endemic family to Australasia, as they should be -- a position also

adopted unanimously by the ABA Rules Committee), and I push the Neotropics

a bit farther north in Mexico (thus all the furnarids and wood-creepers

are Neotropical endemics) while retaining the Caribbean in the Nearctic.

But these are mere quibbles in the grand scheme of things. Thinking of

the World as divided between my nine distinctive "realms" gives me a sense

of order that is comforting. [Of course, in the "real" world -- including

evolution -- is anything but orderly.]

Each of my "realms" has a web page featuring

-

a gallery of photos of places distinctive

to that Realm

-

a brief summary of the literature for that

Realm [handbooks, field guides, journals, and a non-birding book]

-

my picks for the "best birds" of the Realm

[with some explanations] -- in order to end up with a "top 50" birds of

the world, I have allocated the "best bird" picks this way: 10 each to

the Neotropics & Asia, the richest Realms in bird species; 7 each to

Africa, Australasia, and the Oceanic Islands realms; 3 each to North America

& the Western Palearctic (where bird diversity is much less without

tropics), 2 to the Oceans realm (limited to pelagics), and 1 to Antarctica.

[Linked essay on evaluating

"best bird" picks]

-

a link to a page with my 3 "favorite photos"

from that Realm [these are obviously limited to my own shots, but some

are quite nice and some are just important to me]

Again, those Realms are:

BIRDING THE WORLD [some thoughts]

We live in a golden age. We are very lucky to be alive between the time

when all the world's great birds were almost inaccessible, and the time

when many may be gone forever. It is frightening for me to realize that

at my (comparatively) young age of 47 years, I've already seen three species

of birds that have already extinct in the wild. True, the California Condor

may be on the way back to recovery with the captive breeding program (and

some captives have been released back into the wild carrying bands and

transmitters), and the Guam Rail still exists in captivity in another breeding

effort. But the Guam Flycatcher Myiagra freycineti is gone for good.

No amount of money or time or access or inside tips will get you a Guam

Flycatcher. I shudder for generations to come.

Yes,

we are on the cusp between the good and the bad. Except when political

troubles intervene, one can now get to almost anywhere in the world. In

the 1970s, I thought the Arfak Mts. of Irian Jaya, New Guinea, were the

end of the earth -- totally inaccessible both politically and practically.

The endemics there were out of reach. Now its the 1990s; I've spent a week

in the Arfaks; I've seen a good chunk of the endemics. What a great time!

Yes,

we are on the cusp between the good and the bad. Except when political

troubles intervene, one can now get to almost anywhere in the world. In

the 1970s, I thought the Arfak Mts. of Irian Jaya, New Guinea, were the

end of the earth -- totally inaccessible both politically and practically.

The endemics there were out of reach. Now its the 1990s; I've spent a week

in the Arfaks; I've seen a good chunk of the endemics. What a great time!

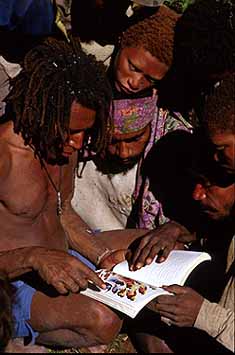

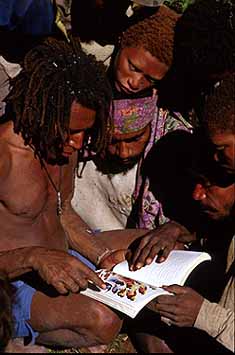

Further, the literature on world birding is exploding. We now have great

field guides to most regions of the world, even those that had nothing

portable when I first visited in the 1980s. The dichotomy that is today

is captured by Will Betz' great photo of New Guinea locals leafing through

the new field guide for New Guinea (right; taken on the Huon Peninsula,

14 mi. south of Teptep, Papua New Guinea, in July 1997 © Will Betz).

New handbooks or family tomes are published almost every month. A good

overview on the world & regional handbooks recently published or underway

is in Salzman (1999). I have highlighted these and other sources on the

Realm pages, including great new sources of information and entertainment

as the Neotropical Bird Club,

the African Bird Club, and

the Oriental Bird Club.

Stuart Keith wrote a wonderful article in Birding magazine in

1974 that had great impact on me. Entitled "Birding Planet Earth," it talked

about how many species of birds there were (then estimated at 8,600; now

thought to be about 10,000). The difference is due primarily to changing

philosophies in taxonomic concepts [an essay on taxonomy and similar topics

is here] and the

challenges involved in finding any significant percentage of them. He asked

"is 7000 possible?" for any single observer? Little did he know that rapid

advances in technology, in transportation, in politics, and in birding

expertise would allow dedicated world birders to surpass 7000 and then

8000. Little did he anticipate that the first one over 8000 would be a

retired schoolteacher from Missouri (Phoebe Snetsinger) who took up birdwatching

at a time she thought (taking her doctor's word) that she had only a few

months to live!

Keith also highlighted some of the great birds of the world. In talking

about the difficulty in locating many species, he made this classic statement:

"Tough birds like Yellow Rail, Boreal Owl and Ross's Gull are a snap compared

to elusive myths like the Congo Peacock, the Long-tailed Ground-Roller

of Madagascar and the Great Argus Pheasant of southeast Asia." I have wanted

to see the Peafowl, Ground-Roller, and that Pheasant ever since -- and

fortunately I'm two-thirds of the way there! [only the Congo

Peafowl remains elusive on a personal level... and likely always will....].

To tour or not to tour?

This is a good question, and the answer will be different for each individual.

Tours (at least the good ones run by Field

Guides, or Wings, or VENT,

or KingBird (phone 212-866-7923), or Sunbird or others (in U.K.), or other

high quality professionals like such small family-run companies as Cheesemans'

Ecology Safaris) are led by very experienced birding guides, usually

with a good collection of tape-recordings, and with specialized knowledge

of the areas to be visited. The company takes care of all your food and

accommodations and, if you wish, your airline reservations. You are likely

to see more species of birds on a tour than a similar length trip "on your

own" to the same area, even if you are well-prepared with detailed bird-finding

information and tapes of your own.

However, by taking a tour, you are stuck with whatever group of other

people happened to join that trip, and sometimes this mix of personalities

or varying levels of expertise or energy will wipe out all the tour's advantages.

You are basically "buying birds" and missing out on the excitement of finding

and identifying your own birds. You will have to share all the big optical

equipment (many leaders carry high-powered scopes) with everyone else,

so while you get great views they are often very quick and hurried. You

will miss some birds because you were at the front or back of the line

in the forest, or in the van, or in the canoe -- engendering a level of

frustration in some that is much worse than not knowing the bird was just

there.

Trips on your own have a lot more hassles with planning, accommodations,

transportation, and figuring out just what that damn bird is anyway (it's

not in the guide!!). But on your own you get the indescribable joy of finding

and identifying your own bird; of choosing to linger over a great view,

or follow a bird to watch behavior, or have time to take photos; of setting

your time and pace.

Perhaps the best of all worlds are small groups of friends that travel

together, share expenses and experiences, and delegate the duties among

the group. These types of trips were more common, it seems, back at the

time of Stuart Keith's article (1974); now, it seems harder to put together

such groups because so many are just taking the tours.

I am often uneasy on tours. I really like finding my own birds; I want

to walk forest trails alone; I don't see the point of some rigid scheduling.

I want to go after the special endemic bird in prime morning hours instead

of dawdling along roadsides with flocks of common species, and I don't

understand the birdwatchers whose every life bird is equally pleasant.

I don't have a lot in common with those who just want to tick off birds

on their checklist, and learn nothing about them or their identification.

There are a lot of these folks on tours. I am uncomfortable with leaders

who are patronizing. [Having said all that, I have been on good tours with

great leaders, including Bret Whitney, Kevin Zimmer, Patrice Christy, and

Terry Stevenson, among others.]

I do enjoy a certain level of comfort -- even in the third world when

possible -- and so do not sleep in the car, do not subsist on peanut butter,

nor skip the morning coffee or the evening beer. I have maniac friends

who readily do all those things to see birds. I have spent nights in native

huts in New Guinea, or slept in hammocks in the Amazon Basin, and marched

through a lot of mud -- but these measures are taken when that is the best

options available. If there is a nice lodge in which to stay -- with a

bed, mosquito netting, and a fan -- I'll take that any day.

Safety is also always a concern. Tours seem to offer more safety, but

I know of instances when birders have been assaulted on tours to New Guinea

and bitten by poisonous snakes on tour in Peru. A friend of mine was killed

by a tiger while leading a tour to India. There are also the horrible examples

of tourist killings by rebels in natural areas of Uganda while on tours.

Yet single birders & small groups have also encountered danger. A British

birder was killed by the Shining Path insurgents in Peru a decade ago;

more recently, American birders were held hostage by rebels in Colombia.

Birders I know have been robbed and beaten in Costa Rica, shot in the Florida

everglades, or suffered burglaries in their motel rooms in Australia. I

had all my luggage, camera gear, exposed film and passport stolen from

a van in Venezuela while at lunch (which is why I can't show the nice Sunbittern

photos I'd taken on the trip). These tragedies can occur anywhere -- even

in your home town. I do not consider world birding to be particularly risky

if one takes some common sense precautions, but it is wise to know the

politics of an area you plan to visit. Peru was dangerous for a time, but

is now much safer. Africa has perhaps become more dangerous recently. Irian

Jaya was closed to western tourists for much of the century, open for a

few short years, and then closed again. Cuba is now hosting visitors. Times

and circumstances do change.

So, for me, there is no clear answer. I go on my own (or with my partner

Rita) or in small groups when I can. However, there are places in the world

that require languages, logistics, expertise, and red tape that would be

exceptionally difficult to handle alone, and for those places I have taken

tours. To Madagascar, and to Sumatra, and to Gabon, or Irian Jaya, for

example. But trips to Malaysian Borneo, Papua New Guinea, Ecuador, Peru,

Caribbean, South Africa, Kenya, Australia, New Zealand, and New Caledonia

have all been undertaken alone or with just 1-3 friends. As always, moderation

and common sense are the better part of the solution.

A final note: I trust that no one

who reads this far will think that I am somehow one of the world's top

birders. Far from it! I'm interested and I've traveled a bit, but have

much less experience than many others. True top world birders are included,

though, among my friends. Bret Whitney has managed to make a living leading

bird tours, but has greatly contributed to science between tours. He has

discovered new species of birds in Brazil, Madagascar, and elsewhere, and

studied the biology & ecological requirements of many obscure tropical

species while remaining comfortable with the North American avifauna. Peter

Kaestner joined the American diplomatic corp and has been posted to Africa,

New Guinea, and South America, becoming an established expert on each continent;

he also discovered a new species to science. The late Ted Parker, with

whom I birded in his hometown of Lancaster, PA, back when he was a teenager,

became the world's best neotropical birder before his untimely death in

a plane crash while doing bird surveys. Tom Schullenberg, whom I knew from

California birding in the 1970s, has taken up some of Ted's "rapid assessment"

projects in the South America wilderness while separately becoming a world

expert on Madagascar. Brian Finch left overcrowded Britain to take a management

job in Papua New Guinea and was widely regarding as "Mr. New Guinea" before

he moved to east Africa; the last time I ran into him was in the field

in Ecuador! Stuart Keith, a Brit transplanted to America, focussed his

studies on Africa and is a leader in the Birds of Africa handbook

series. He was among the first to travel the world widely to learn about

all its birds. These are among the world's top birders.

Beyond this top rank, there are hundreds of birders with enough time

and money to have traveled much more than I; some take up to 6-8 foreign

trips a year [I'm lucky to manage one every two years]. Other energetic

birdwatchers without family, mortgages, or permanent jobs are able to travel

months at a time. Yet another set are full-time tour leaders to far distant

destinations. All these observers have added much to our understanding

of our planet. I'm just fortunate to have followed in some of their footsteps.

Literature cited:

Austin, O. L. 1961. Birds of the World: A Survey of the

Twenty-seven Orders and One Hundred and Fifty-five Families. Golden

Press, New York.

Keith, G. S. 1974. Birding planet Earth -- a world overview. Birding

6: 203-216.

Salzman, E. 1999. Bird books of the golden age. Birding 31: 38-55.

TOP

BACK TO HOME

PAGE

BACK TO LIST OF

BIRD FAMILIES OF THE WORLD

Yes,

we are on the cusp between the good and the bad. Except when political

troubles intervene, one can now get to almost anywhere in the world. In

the 1970s, I thought the Arfak Mts. of Irian Jaya, New Guinea, were the

end of the earth -- totally inaccessible both politically and practically.

The endemics there were out of reach. Now its the 1990s; I've spent a week

in the Arfaks; I've seen a good chunk of the endemics. What a great time!

Yes,

we are on the cusp between the good and the bad. Except when political

troubles intervene, one can now get to almost anywhere in the world. In

the 1970s, I thought the Arfak Mts. of Irian Jaya, New Guinea, were the

end of the earth -- totally inaccessible both politically and practically.

The endemics there were out of reach. Now its the 1990s; I've spent a week

in the Arfaks; I've seen a good chunk of the endemics. What a great time!

This is simple enough in practice, and the result is not far distant from

the faunal map I studied as a youngster (in Austin's Birds of the World

1961; reproduced here). My major differences from the old Birds of the

World map is assigning eastern Russia & China to the Asian Realm;

included New Zealand among the Oceanic Islands instead of Australasia but

assigned Halmahera and the Moluccas to Australasia (thus the Birds of Paradise

are an endemic family to Australasia, as they should be -- a position also

adopted unanimously by the ABA Rules Committee), and I push the Neotropics

a bit farther north in Mexico (thus all the furnarids and wood-creepers

are Neotropical endemics) while retaining the Caribbean in the Nearctic.

But these are mere quibbles in the grand scheme of things. Thinking of

the World as divided between my nine distinctive "realms" gives me a sense

of order that is comforting. [Of course, in the "real" world -- including

evolution -- is anything but orderly.]

This is simple enough in practice, and the result is not far distant from

the faunal map I studied as a youngster (in Austin's Birds of the World

1961; reproduced here). My major differences from the old Birds of the

World map is assigning eastern Russia & China to the Asian Realm;

included New Zealand among the Oceanic Islands instead of Australasia but

assigned Halmahera and the Moluccas to Australasia (thus the Birds of Paradise

are an endemic family to Australasia, as they should be -- a position also

adopted unanimously by the ABA Rules Committee), and I push the Neotropics

a bit farther north in Mexico (thus all the furnarids and wood-creepers

are Neotropical endemics) while retaining the Caribbean in the Nearctic.

But these are mere quibbles in the grand scheme of things. Thinking of

the World as divided between my nine distinctive "realms" gives me a sense

of order that is comforting. [Of course, in the "real" world -- including

evolution -- is anything but orderly.]