comments by D. Roberson

I recently had the good fortune to scope a dark juvenal Short-tailed Albatross Diomedia albatrus from shore at Pt. Pinos & Pt. Joe (it was headed south past Pt. Pinos for prolonged views, then Rita Carratello & I drove to Pt. Joe -- the next major point south -- and picked it up again for more views), as did a number of fortunate observers over the period 1-10 May 1999 (Craig Hohenberger, Jim Teitz, Dave Haupt, Bill Hill, Tom Lowe; it is possible two different birds were involved). I now have my written details plus those of several others, and there are interesting points about shape and flight differences that have not previously been published. While some had the bird close enough (Tom Lowe) or at the right angle (Craig Hohenberger) to see the huge pink bill on an otherwise all-dark bird, must (including me) had only silhouetted views out to the west late in the afternoon. The winds typically pick up in late afternoon in Monterey Bay, and it is fairly routine to see Black-footed Albatrosses from shore on windy days from these points. The period 1-10 May 1999 was exceptionally windy (up to gale force 9 May) and dozens for Black-foots were visible during any prolonged period of scoping.

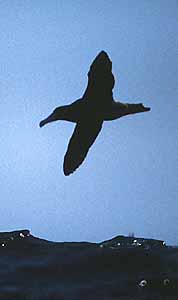

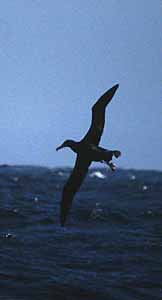

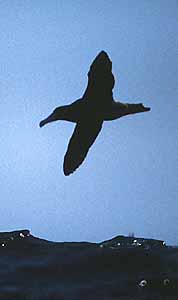

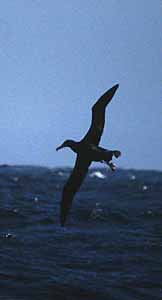

On this page I compare three photos of Black-footed Albatross with three photos of juvenal Short-tailed Albatross. The bottom row has two silhouetted shots of a bird I photographed over the Cordell Bank, Marin Co., in Nov 1985; the bottom right shot is by Ron Branson of the Dec 1998 Monterey Bay bird (which could possibly have remained to account for the May 1999 sightings).

A discussion of identification of dark albatross in the north Pacific must begin will a full understanding of Black-footed Albatross D. nigripes. One must first have full confidence in one's experience with this common species. As albatrosses go, it is a fairly small one, but it is, of course, the largest procellarid regularly seen in Monterey Bay, and therefore looks "huge" compared to all our shearwaters, petrels and fulmars. Young birds are quite blackish-slate with black bills & feet (upper left), older birds have variable amounts of white on the face, uppertail coverts and undertail coverts (upper middle) while some extreme (very old?) birds have much more extensive white to the head & underparts (upper right). In all plumages, though, the upperwings and underwings are entirely dark except for pale bases to the primary shafts (visible in slightly in all shots) and irregular patchiness caused by molt (upper middle).

Juvenal Short-tailed Albatross is a much larger bird than Black-footed, but this can be difficult to determine unless the species are adjacent. Young Short-tailed has a huge "bubble-gum pink" bill (sometimes with a dusky tip) and very dark chocolate-brown plumage. In contrast to Black-footeds, which get white around the base of the bill, and on the uppertail and undertail coverts very rapidly, the head, uppertail coverts, and undertail coverts of Short-tailed Albatross are the darkest parts of the bird. Some juvenal Short-tails will appear to have a slightly paler belly or chest (bottom right) or slightly paler upperwing coverts (which will become white in the following plumage in sequence; see Roberson, 1980, Rare Birds of the West Coast), but the head, uppertail, and undertail coverts are always very dark (as was apparent on the bird we scoped on 10 May).

Look at the difference in size and shape of the bill in silhouette. It can often be impossible to determine bill color in silhouette (bottom row, left & center photos; the righthand photo is not directly silhouetted). On Black-footed, the bill is fairly "balanced" to the size of the fairly small head and the bill is not longer than the head. At 1/2 mile distance, the bill of Black-footed Albatross basically "disappears" and an obvious Black-footed on the horizon -- still easily identified as an albatross -- may look "bill-less" [we had ten Black-foots on the day we watched the Short-tailed, and this feature was readily apparent]. In contrast, the bill of Short-tailed is both long and huge, even though the head itself is quite large and boxy. The bill dominates the silhouetted head (lower left) and is obvious under all circumstances, even at long distances. It is decidedly longer than the head and so thick at the base that it can be hard to tell where the bill ends and head begins (lower middle).

Black-footed Albatross at long distances look exceptionally long-winged, thin-winged, and show a prominent "crook" in the wing about 2/3 to 3/4 out the wing (all three upper photos). The wings are always bent at this "wrist", and because of this the flight is very buoyant and dashing (for an albatross). The wings are even further bent in a wing-stroke (upper left). In contrast, a Short-tailed Albatross looks proportionately short-winged, broad-winged, and without much (if any) crook in the wing (lower left and right). When the wings are bent at all (e.g., the lower middle shot as the bird banks in for a landing behind the boat -- not that the feet are extended in this maneuver), the bend is less far out the wing -- perhaps a just little over half-way to two-thirds out the wing -- and the wing itself is much less flexible. Tom Lowe's description notes that "it looked bigger and broader winged than the other albatrosses. As it came closer, I realised the wings were also held much straighter, lacking the familiar carpal angle than the Black-footed Albatrosses tended to show." I noted "decidedly broader wings" than Black-foots, the latter having "long, thin wings with a prominent angle 3/4 out the wing" visible on the horizon.

These wing differences produces a different flight in Short-tailed in wing conditions in which Black-footeds are particularly fast & buoyant. Tom Lowe says that his bird "flew in a much more leisurely manner, soaring up into the wind and falling back towards the east before recommencing its westward progress" (this was in particularly strong gales) while it strong windy conditions (but less than gale-force), Haupt described the flight as "regular wing beat that were slow and lumbering, seeming to bend at bird's upper wing, not just at the wrist" while I described the flight as "more even and lumbering, at a steady predictable pace above and below horizon, whereas the Black-foots were arcing up higher and flying faster and more agilely, on more prominent bent wings, down into the troughs."

I noted another feature that was quite prominent, and shows well in the series of photos above. Short-tailed has a "pot-bellied" look, is quite thick at the rump, and very broad-tailed. This gives the bird a "back-loaded" effect -- despite the huge bill -- as more the bird seems to stick out behind the wings than in front. Even Black-foots with spread tails (upper middle) look to be "balanced" fore-and-aft of the centrally-placed wings, and the tail is set off by white uppertail coverts (and white undertail coverts from below). Short-tails seemed to have huge tails and stout lower bodies which are decidedly thicker than the big neck/head/bill is full ventral profile (lower middle & right). Perhaps no single feature was on the 10 May bird impressed me as much as this. [At closer range the big pink feet should be looked for.]

Rollo Beck wrote (1910, "Water Birds of the Vicinity of Pt. Pinos," Cal. Acad. Sci., 4th series, p. 65) that "only on one occasion, December 12, 1904, did I see an albatross that might have been this species [Short-tailed Albatross]" but he reported that "Mr. Loomis, however, found it quite common in the winter of 1894 and 1895 and in the fall of 1896." A century ago, in the 1890s, it was considered the easier albatross to see from shore. The species was almost extinct due to plume hunters on its breeding island (Torishima, off Japan) by the end of World War II, but with protection it is now on its way back. Government estimates last year were 500 adults and perhaps 1000 birds total.

Short-tailed Albatross are increasingly being seen in Alaska; some details and photos of recent birds are found at the links of this "Short-tailed Albatross page." Among those Alaskan birds are plumages beyond juvenal plumage.

Little

has been published about plumage sequences; I have recently read that it

takes 12 years to reach maturity. The sketches in Rare Birds of the

West Coast were patterned on those by N. Yanagisawa in the Japanese

magazine Yacho (Vol. 38: 44; 1973), and may represent a generalized

pattern, but they may also be incorrect in several respects. These photos

of a captured bird held briefly at the San Francisco Zoo in 1971 give us

a clue of what to expect. The forehead, face, chin, throat and front of

neck become clearly white, neatly demarcated from the otherwise dark body.

Note that the uppertail coverts and undertail coverts remain dark (very

different than Black-footed), and the belly is still dusky. Upperwing coverts

begin to some whitish mottling where a larger white patch will develop,

but the underwings remain dark. Whitish primary shafts become prominent.

Little

has been published about plumage sequences; I have recently read that it

takes 12 years to reach maturity. The sketches in Rare Birds of the

West Coast were patterned on those by N. Yanagisawa in the Japanese

magazine Yacho (Vol. 38: 44; 1973), and may represent a generalized

pattern, but they may also be incorrect in several respects. These photos

of a captured bird held briefly at the San Francisco Zoo in 1971 give us

a clue of what to expect. The forehead, face, chin, throat and front of

neck become clearly white, neatly demarcated from the otherwise dark body.

Note that the uppertail coverts and undertail coverts remain dark (very

different than Black-footed), and the belly is still dusky. Upperwing coverts

begin to some whitish mottling where a larger white patch will develop,

but the underwings remain dark. Whitish primary shafts become prominent.

Additional photos of Black-footed and Short-tailed Albatrosses are now on the albatross page of my web site.

Some have wondered how we could eliminate all other albatrosses for the Pt. Pinos birds if the bill color was not seen. The discussion above shows how Black-footed was surprisingly easy to eliminate. As for the others, that too is not difficult. Black-footed Albatross and juvenal Short-tailed Albatross are the only all-dark square-tailed albatrosses in the world. The two species of Phoebetria of the southern hemisphere -- Sooty Albatross and Light-mantled Albatross (of which there is one photographed bird in California) -- are rather small albatrosses with very small delicate bills and long, wedge-shaped tails. Waved Albatross (from the Galapagos) has an extensively white head/breast and white underwings. Young Wandering and Amsterdam Albatrosses may be mostly dark-bodied, but have white faces and (more importantly) almost entirely white underwings (see photos in Harrison, 1987, Seabirds of the World: A Photographic Guide). The rest of the world's albatross are white-bodied. Even in full silhouette, any white-bodied albatross would have been plainly visible as such, as well as any with extensively white underwings or heads.

We are now fortunate indeed to be entering the time when we can again be anticipating the occurrence of the long-absent Short-tailed Albatross with some regularity.

Photos: Black-footed Albatross were in Oct 1987 (upper left) and Aug 1990 (upper middle), both on Monterey Bay, California (photos © D. Roberson), and Sep 1971 off Westport, Washington (upper right; © Dennis Paulson). Short-tailed Albatross were on 5 Nov 1985 over Cordell Bank, California (lower left & middle; © D. Roberson) and 21 Dec 1998 about 3 miles W of Pt. Pinos, California (lower right; © Ronald L. Branson). The photos of the zoo individual were taken June 1971 (standing bird; © Ron LeValley) and May 1971 (wingspread shot; © Mike Wihler).