| |

|

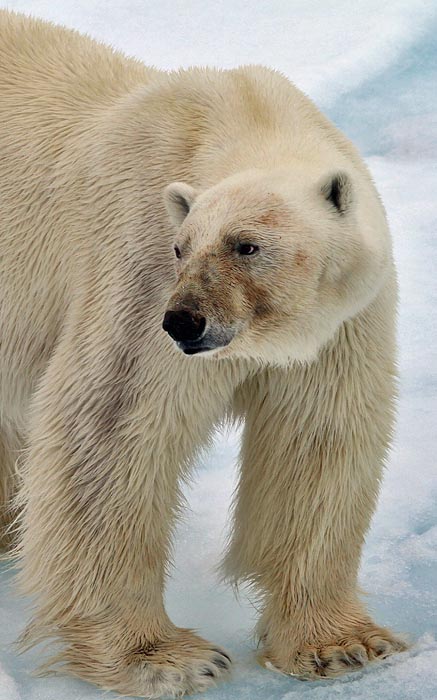

Polar Bear on ice-sheet north of Spitsbergen 29-30 June 2013 (two different bears shown) © Don Roberson (all photos) |

Polar Bear Ursus maritimus

is the largest land predator on earth. It is a huge carnivorous bear

that averages larger than Brown Bear. Adult males weigh 350-75 kg

(770-1500 lbs) while an adult female is about half that size. The

largest recorded male was shot in northwest Alaska in 1960, weighed

1002 kg (2209 lb) and stood 3.4m (11 ft) tall when mounted on its

hindlegs (Wood 1973).

Despite the claim of

“largest land predator,” Polar Bears can be called "marine mammals."

Much of their life is spent on the sea-ice and they swim readily and

easily. They routinely cross large bodies of ocean and have been seen

in the Arctic Ocean 300km (200 mi) from land. They concentrate at the

edge of the polar ice-pack, where their prey [primarily Ringed Seals Pusa hispida and Bearded Seals Erignathus barbatus] is most abundant.

For

the most part, humans are few within the Arctic range of Polar Bear,

and deadly confrontations are few. Humans kill far more bears than

bears kill people. Yet, Polar Bear is a very dangerous animal. Bears

are fearless towards people; they are very curious and are

unpredictable in temperament; and in the right circumstances one will

stalk, kill, and eat a human as prey. Many attacks by Brown Bears are

the result of surprising the bear, but this is not the case with Polar

Bears. These alpha predators are stealth hunters and a victim is often

unaware of the bear’s presence until the attack is underway. Whereas

Brown Bears often maul a person and then leave, a Polar Bear attack is

more likely to be predatory and is almost always fatal; Stirling

(1988). Yet, man is not a preferred prey and attacks may be by hungry

bears in unusual circumstances.

While Polar

Bears have attacked large mammals like Svalbard Reindeer or even

Musk-ox, their biology requires a large amount of fat from marine

mammals; there are insufficient calories in terrestrial food; Ramsey

& Hobson (1991), Ovsyanikov 1996. Humans are at a huge disadvantage

in the barren and frozen habitat of Polar Bears. A bear can smell a

seal a mile away and in a den buried under 3 feet of snow. It can smell

a human a long way off. It has good hearing and excellent vision. It

knows how to blend into the habitat through cunning and stealth. A bear

can outrun you. Man’s only significant defense is a gun. In places like

Svalbard, north of Norway, people are warned at the edge of each town

that this is Polar Bear country – enter at your own risk. Even wildlife

tours to Arctic Svalbard routinely have leaders carrying guns at all

times – and posted as look-outs – any time tourists are permitted off

ships and come ashore.

|

|

|

| Despite

all this, people can have fabulous interactions with Polar Bears from

safety. In Churchill, Manitoba, Canada, drivable Tundra Buggies take

tourists in comfort to bear congregation sites in late autumn. There

are camping expeditions to the Arctic in summer that observe bears from

a distance; the boneyard at Pt. Barrow, Alaska, is also well-known as a

spot to sometimes see individual bears with the protection of a guide

with a gun. More recently, Arctic cruises in North America, Greenland,

or Svalbard offer excellent encounters with bears from ships able to

enter the ice-pack in summer, or from zodiacs cruising bays and shores

on the mainland.

The photos here were taken on a

Svalbard cruise. Curious bears may come right up to the ship when

within the ice-pack; during our cruise an outdoor barbeque on the

fantail of the ship attracted a big male (middle photo). If one is very

lucky (as we were) one might observe predation of seals and

interactions between bears. Polar Bears hunt seals in three distinct

ways: (a) they smell a baby seal in a birth-chamber under the snow and

dig it out; (b) they wait at an air-hole until a seal surfaces for air

and grab it with a powerful swipe of its paw [in fact, a Polar Bear has

been documented pulling a Beluga from an ice-hole when the whale

surfaced for air]; or (c) they stalk a seal resting on the ice. Bears

often approach lounging seals by swimming or by stealth. We saw several

instances of bears feeding on a seal carcass on the ice-sheet north of

Svalbard, but in each case the seal was already dead when we arrived.

Most dramatically, we watched a large male chase an adult female off

her kill. She had killed a large Bearded Seal (photos top & bottom)

that was larger and heavier than she was. The male bear chased her off

and then chose to pick up the carcass — which appeared to weigh more

than he did — and carry it some distance on the ice to be devoured at a

spot that he preferred. Truly an impressive show of immense strength! |

|

Polar Bear on ice-sheet north of Spitsbergen 29-30 June 2013 (with Glaucous Gulls and Ivory Gull) © Don Roberson (above) |

| |

Brown Bear at Brooks Falls, Katmai NP, Alaska 30 June-1 July 2011 © Don Roberson (below) |

|

Brown Bear at Brooks Falls, Katmai NP, Alaska 30 June-1 July 2011 (four different bears shown) © Don Roberson (all photos) |

Brown Bear Ursus arctos

is the alpha predator across the forested Holarctic. There are several

subspecies but their limits are subject to debate. Genetically, it

appears that in the Old World there are two clades within the nominate

subspecies, and others in Central Asia. In North America, there are 3

or 4 clades (including a California clade that is extinct); Garshelis

2009). Within the subspecies currently called Ursus arctos horribilis,

two groups are generally recognized—the coastal Brown Bear and the

inland Grizzly Bear -- these two types broadly define the range of

sizes of all brown bear groupings. An adult Grizzly living inland in

Yukon may weigh as little as 80 kg (180 lb) while an adult coastal

Brown Bear living on a steady diet of spawning salmon may weigh as much

as 680 kg (1500 lb). Obviously it is these huge bears that appear to be

the most scary. Yet, the abundance of salmon, especially during the

summer spawn, focuses the attention of these bears and their

interactions with people at such places are mostly without incident.

One of those locales is Brooks Falls, Katmai NP, Alaska, where these

photos were taken.

It seems in the incidence of

bear attacks is primarily inland, perhaps due to limited food and

hungry bears, or perhaps because it is easier to come unexpectedly upon

a bear inland. Brown Bears do not take well to surprise. Fatal attacks

by Brown Bears in North America average about two per year (Herrero

2002). The Alaska Science Center (Smith & Herrero 2008) ranks the

following as the most likely reasons for bear attacks: surprise,

curiosity, protection of young, predatory intent, wounded hunted bear,

carcass defense, and provoked charge. Unlike smaller Black Bears Ursus americanus

that can climb trees, adult Brown Bears respond to danger by standing

their ground and warding off their attackers. Mothers defending cubs

are the most prone to attack, being responsible for 70% of Brown

Bear-caused human fatalities in North America (Herrero 2002).

A

wounded bear is a dangerous bear. In 1915, a gigantic male known as

"Kesagake" visited the village of Sankebetsu, Hokkaido, Japan, to feed

on harvested corn. The bear was shot by two villagers and fled to the

mountains, injured. On 9 Dec 1915, Kesagake showed up again, killing 6

people in two days, eating some and stashing others away. A famed bear

hunter finally shot "Kesagake" on 14 Dec. The bear was almost 3m

(nearly 10 ft.) tall and weighed 380 kg (837 lb). Human remains were

found in his stomach. The region was abandoned by villagers for fear of

more bear attacks, and it became a ghost town. Even today, the

Sankebetsu incident remains the worst animal attack in the history of

Japan. Kimura Moritake (1994) published a book on the incident, and

there are Japanese movies and plays based upon the story.

Given

all these concerns, one does not wish to come upon a Brown Bear

unexpectedly, or get between a mother and cub. However, like many land

predators, humans are more a threat to bears than they are to us.

Quammen's Monster of God chapter on bears focused on Brown

Bears in Romania; the purpose of bear reserves there [i.e., as hunting

locales for the rich and famous, and most infamously, dictator Nocolae

Ceausescu; the wardens relationship with the bears and the dictator;

and what happened to all of them.... great reading]. |

|

|

In

Alaska, viewing or photographing Brown Bears at places like Brooks

Falls can be rewarding. The excitement is best during the big salmon

run (usually late June-early August, but it can vary earlier or later

year to year) and reservations must usually be made a year or more in

advance. Lodging (mostly comfortable cabins) is limited and fills up

fast. Meals were great — fresh salmon every day, just like the bears!

The two levels of viewing decks adjacent to and slightly above Brooks

Falls are often crowded with photographers and tourists, and at busy

times one has a limited time at the viewing deck. It is good to come

early or late in the day. Upon arriving at Brooks Lake by float plane

(the only way to get there), one must listen to a mandatory lecture on

living among bears. One is no permitted to carry any food of any type;

fisherman must cut fish off their lines if a bear approaches; and the

pontoon bridge across the river — the only access to the Brooks Falls'

viewing platform — is closed whenever a bear gets too close. When one

watches the situation at the falls for a time, it becomes apparent that

there is a real hierarchy among the bears there. The largest males have

the prime locations and younger bears slink away when one of the big

beasts arrive. At other times there are noisy encounters or actual

fights — the bears shown below are disputing a spot near the falls, and

one bear shows injuries from a previous such engagement.

If

you stay a few days, you may encounter a wild Brown Bear on your own.

The viewing platform and the walkways leading to it are carefully

fenced and above-ground, but many trails in the park are through bear

country. I was alone one morning, slowly birding along one of those

paths, when I heard something running down the trail towards me. Having

taken the mandatory course on arrival, I recognized it was likely a

bear, and stepped back off the trail, next to a tree. Suddenly a

smallish, young-looking bear rushed past me down the trail. But I again

remembered the lecture.... where one bear is running, there is likely

another bear to follow. So I stayed still. And yes, a decidedly larger

bear came trotting past — a mid-sized male — and he stopped to turn and

look at me. Deciding that I was less interesting than the female bear

in heat which he was chasing, he quickly rumbled on again. Later I

heard he had dashed through the main camp and past the dining room in

efforts to locate that young sow. Still — a nice heart-skipping bit of

adventure.

|

|

| |

Click below for the next page of this project

OR use these LINKS to the SPECIES PAGES

|

|

Photos: All photos © Don Roberson, except as otherwise attributed; all rights reserved.

Literature cited:

Garshelis, D.L. 2009. "Ursidae (Bears), " pp. 448 –497 in Handbook of the Mammals of the World, Vol. 1 (D.E. Wilson & R.A. Mittermeier, eds). Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Herrero, S. 2002. Bear Attacks: Their Causes and Avoidance, revised ed. Lyons Press, Guilford, CT.

Moritake, K. 1994. The Devil's Valley, Kyodo bunkaska, Tokyo.

Ovsyanikov,

N.G. 1996. Interactions of polar bears with other large mammals,

including man. Journal of Wildlife Research, 1: 254–259.

Quammen, D. 2003. Monster of God: the Man-Eating Predator in the Jungles of History and the Mind. Scribner, New York.

Ramsay,

M. A., and K.A. Hobson, K. A. 1991. Polar bears make little use of

terrestrial food webs: evidence from stable-carbon isotope analysis.

Oecologia 86: 598–600.

Smith, T. S. and S. Herrero, S. 2008. "Ursus arctos californicus." Alaska Science Center – Biological Science Office.

Stirling,

I. 1988. Polar Bears. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Wood,

G.L. 1973. The Guinness Book of Animal Records. Doubleday, New York.

|

|

|