a web page by Don Roberson |

|

||||||

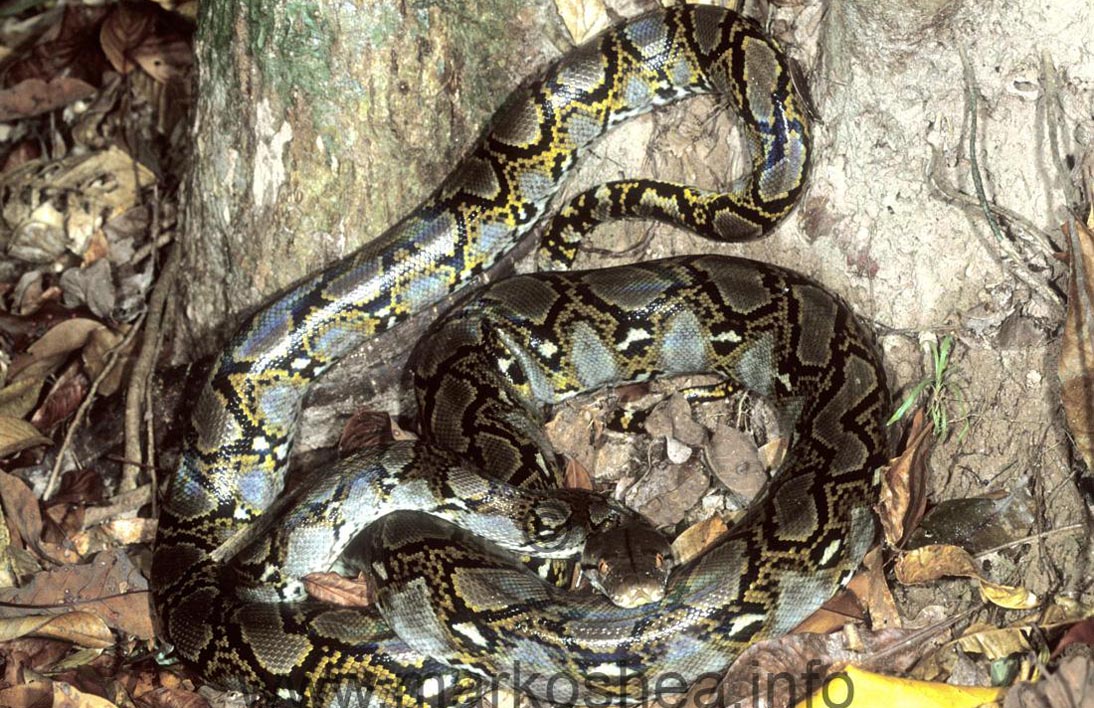

Reticulated Python from 2002 at Tarutao Is., Satun Province, Thailand © Mark O'Shea (above) |

||||||

Reticulated Python Python reticulatus is believed to be the longest snake on earth. It is a huge and beautiful python of southeast Asia, ranging from eastern India to the Greater Sundas, Philippines, and as far east as Halmahera. Although I have seen one (see below), I have no photos. Mark O'Shea, famed herpetologist and author of Boas & Pythons of the World, graciously provided this shot from Thailand. This particular python, Mark recalls, was a "moderately large specimen in the wild; none too friendly either!" [Mark O'Shea's website has a ton of adventures and reptile photos.] The longest snake that ever lived in a zoo was a female Reticulated Python named "Colossus." She was 22 feet long when captured in Siam (now Thailand) in 1949, and brought to the Pittsburgh Zoo. Eight years later she reached the length of 28 feet and her weight was estimated to be more than 320 pounds (a photo is in Pope 1961). It is repeatedly asserted that a Reticulated Python caught on Sulawesi was measured at a length of 33 ft. (9.9m), the longest snake on earth (e.g., Pope 1961). Whether the story of the 33-footer is true is less certain, as the story is apparently based on this quote: "... men at the mine told me of a huge python one of their natives had killed a few days before my arrival, and showed me a very poor photograph of it taken after it had been killed and dragged to camp. The civil engineer told me it was just ten meters (33 feet) long. I asked him if he had paced off its length, but he said no, he had measured it with a surveying tape." Thus it seems that real scientific evidence of a snake longer than 30 feet is lacking; Murphy & Henderson (1979). |

||||||

|

||||||

South Africa Rock Python on 5 Aug 2002 at Tarangire NP, Tanzania © Don Roberson (both photos below) |

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

Central African Rock Python Python sebae is mostly a rainforest species from west Africa to the Congo Basin. O'Shea (2007) gives its maximum length as 4.0 –7.5 m (13–24.6 ft.). Prey recorded for this species includes monitor lizards, porcupines, wild pigs, domestic dogs and goats, crocodiles, and the occasional human (O'Shea 2007). "Large females lay a large clutch of eggs in a termite mound or animal burrow and coiling about them, will incubate them for approximately 90 days. During this time the female will occasionally leave the eggs to bask and then return to the egg clutch to continue incubation. She is also particularly defensive of her clutch and large females we have maintained have chased members of staff who approach too close to their chosen nesting sites. Angry pythons often raise and coil their tail tips and this should be seen as a warning, especially when accompanied by the long, drawn-out hiss;" O'Shea (2007). I have not seen this species, but I am duly warned to avoid tail-twitching, hissing pythons, especially if they are chasing me. |

||||||

|

||||||

Boa Constrictor ~1975 Leticia, Colombia © Van Remsen (above left); Green Anaconda ~1997 Dona Barbara, Los Llanos, Venezuela © Mark O'Shea (above right) |

||||||

The "widest, bulkiest, and heaviest snake in the world" (O'Shea 1997) is an American boa named Green Anaconda Eunectes murinus. Quammen's (2003) book listed three snakes — Reticulated Python, African Rock Python, and Anaconda — among his 15 alpha predators. As we have seen (above), African Rock Python is now split into two separate species. More dramatically, the old Anaconda has now become four (4) species.* But the huge and widespread species of the Amazon Basin and northern South America is Green Anaconda — and that is the snake of which Quammen was thinking. Even long-held assumptions can turn out to be wrong. For over 30 years I have used the now-faded slide shown above left as a photo of an Anaconda being displayed by Mike Tsalickis (to the right), a girl name Amy, and a third helper. Van Remsen had taken this shot in the mid-1970s at Tsalickis's animal menagerie along the Amazon River at Leticia, Colombia. Tsalickis, known a Jungle Mike, was a legendary figure "with stories to tell" who had been featured in Reader's Digest and National Geographic. I met him briefly when I joined Van at Leticia for a birding adventure in 1975. I think it was there that I saw a film of Jungle Mike wrestling an Anaconda in a river. As detailed in a 1993 story in the Tampa Bay Times, Mike's "stories were about Leticia, the Colombian frontier town the man from Tarpon Springs (Tsalickis) all but founded; about giant snakes, which he wrestled for tourists; and about gullible Italians, who seem to believe that he actually stalked, shot and ate the Indians who would have died without the hospital he built for them, way back in the bush." Although I'm sure Mike knew his snakes, I wonder how often he may have passed off a big Boa Constrictor Boa constrictor as an "Anaconda" for the tourists [the photo above left shows a 3m (10 ft) Boa Constrictor, advises Mark O'Shea]. And as to wrestling Anacondas, "the trick," said Tsalickis, "was to keep the snake in the shallows. If he gets you into the deep water, you're through." The Tampa Bay Times article then turns to a sadder story. They quote Terry Furr, an assistant U.S. Attorney who put Tsalickis away for 27 years for cocaine trafficking: "He's the kind of guy, under different circumstances I would have liked to get a couple of beers with him, just to hear the stories." To the upper right is a real 12 ft. (3.65m) Green Anaconda being held by herpetologists Mark O'Shea. It is dark green above with black oscelli-like spots; outlined spots are only underneath. The larger they get the darker and less distinct they appear. Compare the huge Anaconda that Mark was holding to this small, young example (below) that our boatman found along Sucasari Creek, a tributary of the Napo River, near its confluence with the mighty Amazon in northeastern Peru. The boatman hauled it into our small boat for better views. There seems little doubt that Green Anaconda is the largest snake in the world by weight (e.g., a 4.5m Anaconda will weigh as much as a 7.4m Reticulated Python; O'Shea 2007), but there is debate about the longest length. O'Shea (2007) gives a maximum length of 7.5m (24.6 ft.) to 11.5m (37.7 ft.) but there is little confirmed, tangible evidence of the claims of over 30 ft. Females are larger than males; one 5.21m (17 ft.) female weighed 97.5 kg (215 lbs). These are just gigantic snakes. There is also debate about its status as a "man-eater." O'Shea points out there are rumors, rather than verified evidence. Yet, a huge snake in the water which routinely captures and eat mammals as large as tapirs could easily consume humans, especially children, who were swimming. Rivas (1999) published a note, with photos, of two predatory attacks by Green Anacondas on adult human researchers employed by him. Both attacks were by large female Green Anacondas (5m & 4.45m, or ~14-16 ft. long, and 39-54 kg, or 85-120 lbs, in weight) and were judged to be predatory rather than defensive in nature. Even if actual verified evidence of man-eating is lacking, a huge Anaconda is of grave concern "in the jungles of history and our mind," per Quammen's subtitle. Accordingly, as Quammen considered it as a worthy member of his 15 predators, I fully support its placement on this list. * The other species are Yellow Anaconda Eunectes notaeus of the Pantanal, Dark-spotted (or DeSchauensee's) Anaconda E. deschauenseei northeastern Brazil and adjacent areas, and Bolivian Anaconda E. beniensis in Bolivia (e.g., O'Shea 2007). All are smaller species; the first two apparently reach maximum length at 3m (9.8 ft.) and are thus unlikely man-eaters. I have seen the Yellow Anaconda in southern Brazil. |

||||||

|

||||||

Green Anaconda in June 1987 Sucasari Creek near Napo River, Peru © Don Roberson (above) |

||||||

Click below for the next page of this project OR use these LINKS to the SPECIES PAGES

|

||||||

Photos: All photos © Don Roberson, except as otherwise attributed; all rights reserved. Literature cited:

|