|

|

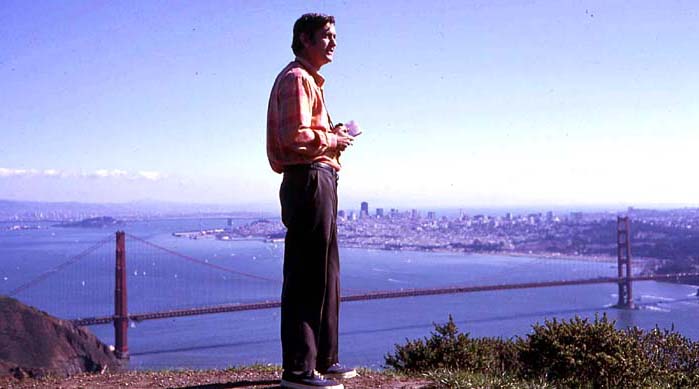

| Laurie Binford was a premier California birder from the late sixties

to the early eighties. He was the primary instigator in the founding of

California Field Ornithologists (which became Western Field Ornithologists;

WFO) and its journal California Birds (eventually Western Birds).

He was the founder of the California Bird Records Committee, wrote its

bylaws, and was one of its most influential members throughout our period

of review. He served on the CBRC for 14 years between 1969-1986, missing

only one year during an enforced bylaw absence. Throughout most of this

time he was Curator of Birds & Mammals at the California Academy of

Sciences, San Francisco, and was vitally important to the birding world

as a professional ornithologist who was also an active birder. At a time

when most professional ornithologists disdained birding and disregarded

sight records, Laurie embraced the growing expertise among field birders

and encouraged them to reach higher standards by adopting means to review

and validate sight records.

Laurie himself was a sharp birder. Growing up near Chicago, spending summers in Michigan, and going to grad school in Louisiana, he had a strong background in eastern and Mexican species: a depth of experience not generally held by home-grown California observers. His expertise was perhaps most notably on display during the infamous 'skylark episode,' detailed elsewhere in this web project, but he exemplified in his own birding the self-skepticism that would later become a part of many a top birder's persona. His ready access to museum specimens helped, of course, but his thorough knowledge of the birds in the field was remarkable. He passed on this knowledge to an entire cadre of young birders in the 1970s, many of whom cite him today as one of their primary mentors. Perhaps Laurie's most important discovery was the Pt. Diablo hawk flight, where migrants hawks concentrated in fall before crossing the Golden Gate and heading south down the California coast. After noting the autumn passage of hawks outside his office at Cal. Academy, he set out to find a concentration point. On 21 Sep 1972 he visited Pt. Diablo and saw 162 individuals of 10 species of raptors in a little over 3 hours. Visits on 29 partial days that fall yielded over 4000 raptors of 14 species, concentrations that rivaled the famed Hawk Mountain in Pennsylvania. Today, the Pt. Diablo hawk watch is the most famous observatory in western North America. Laurie was meticulous in his projects. Anything he put his hand to would

be superb, but each project took (seemingly) forever. It took him over

20 years to publish his PhD research on the birds of Oaxaca, Mexico (Binford

1989). The papers that he wrote with Van Remsen on Yellow-billed Loon (Binford

& Remsen 1974, Remsen & Binford 1975) were excellent examples of

meticulously written and researched papers.

|

|

Among

aspects of birding that interested Laurie was the quantification and analysis

of records. Determined to better understand the birds of Golden Gate Park,

for example, he prevailed on local birders to do a hardcore "Christmas

Count" of Golden Gate Park one winter Saturday. But unlike usual CBCs,

participants were required to actually count every single bird — no estimates.

I personally learned a lot by lending a hand to that project; Bushtit flocks

in winter, for example, were variable but averaged about 13 birds. Among

aspects of birding that interested Laurie was the quantification and analysis

of records. Determined to better understand the birds of Golden Gate Park,

for example, he prevailed on local birders to do a hardcore "Christmas

Count" of Golden Gate Park one winter Saturday. But unlike usual CBCs,

participants were required to actually count every single bird — no estimates.

I personally learned a lot by lending a hand to that project; Bushtit flocks

in winter, for example, were variable but averaged about 13 birds.

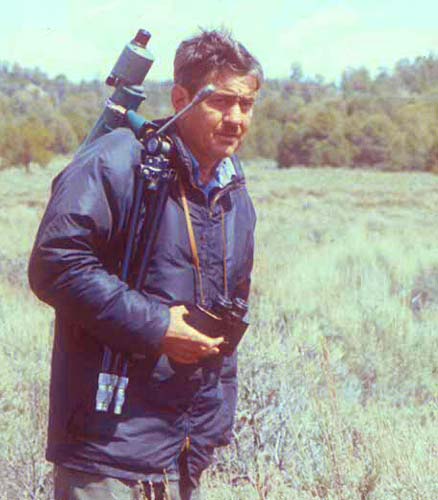

Laurie was active in many important organizations. He was President of the Board of Directors of Pt. Reyes Bird Observatory (1972-1976), President of WFO (1983-1986), Secretary of the Cooper Ornithological Society (1978-1981), and a member of the ABA's checklist committee (1985-1992). But Laurie also enjoyed the lighter side of birding. He participated in many Big Days throughout the '70s and '80s, often with his friend Mike Parmeter and, in the '80s, Mike's son John, among others (Rich Stallcup, Van Remsen). He was a member of the record-tying California Big Day in 1983, and the record-setting California Big Day team in 1984. There is a story, perhaps apocryphal, that highlights Laurie's depth of knowledge. In 1987, Laurie was invited to be among the tour leaders on Attu Island, at the western end of the Aleutians, Alaska, where many birds representing first North American records were being discovered during the annual spring visit. Unbeknownst to him, some practical joker had brought a single feather along to test the leaders. Arranging for an innocent beginning birder to "discover" the feather during a day's outing, it was presented to all the leaders for possible identification: "I picked this up today at Murder Pt. — does anyone know what it is?" And no one did until Laurie stroked his chin and said "If I didn't know we were in Alaska, I'd say this was from an Oilbird" [a nocturnal Neotropical bird assigned to its own monotypic family]. Of course, that's what it was. Laurie had ruined the joke — he knew TOO much. Beyond all the knowledge, Laurie was known for a wry sense of humor (often deprecating the lack of good birds about), an ever-present cigarette, and his Manhattan or glass of Louis Jadot Beaujolais after birding . And Laurie could golf — indeed, it was an annual ritual to attend the then Bing Crosby tournament at Pebble Beach. After retirement in the mid-1980s, Laurie returned to the Midwest. He splits his time between northern Michigan in summer (his book on the Keweenaw Peninsula is in the works), and Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in winter, where he has become one of the local hummingbird experts. Photo (left) 28 Apr 1984 Big Bear Lake SBE © B.B.

Roberson

|

|

Official Bird Name: Brown-backed Solitaire (Texas-given name) or Grayish Mourner (California-given name; alas the photo shows only a relative, a piha)

Selected publications 1971-1989:

|

|