a web page by Don Roberson |

|

Update [Feb 2025]: |

THE PROJECT: Fifty Best Civil War sites At the beginning of Ken Burns' (1990) wonderful PBS series The Civil War, narrator David McCullough intones: "The Civil War was fought in 10,000 places, from Val Verde, New Mexico, to St. Albans, Vermont, to Marianna, Florida . . ." It is not possible to visit 10,000 places, but if one wishes to get a first-person view of the more important Civil War sites, one must prioritize. Indeed, neither Val Verde nor St. Albans nor Marianna appear on this "top 50" list. People and nature have already removed a majority of the 10,000 places, even some of the most important ones. I enjoy visiting important Civil War sites. From my home in California, it is no easy thing to undertake these visits. Each trip "back East" is a major vacation, and yet my wife Rita Carratello and I have done at least five ttips with a hefty focus on Civil War sites in the last three decades, scattered among trips around the world to seek out birds and mammals [trip reports of those elsewhere on this web site]. I decided it would be fun to prioritize and rank those Civil War sites I had seen, balancing the criteria between visitor experience and the importance of the battle to the War. Small battles could be ranked highly if exceptionally well-interpreted; large battles might slide in the ranking if the visitor experience was impaired by encroachments, busy roads, poor signage, or neglect. This is, of course, just one person's opinion.

There are at least 410 Civil War sites listed on a prior Internet compilation. I have visited most important Civil War sites. I've been to the vast majority of the National Park Service sites, and a fair number were visited two or more times. Fortunately, there is a recent upsurge in preservation, and new sites are becoming accessible to the public annually. On the pages that follow are my choices for the "50 Best Civil War sites." For each there is a short explanation of the battle and a site review; a photograph (all but one taken by me — the exception is the interior of the Confederate White House); and the dates of my personal visits to the site. In choosing photos, I have tried to recognize that while the "cannon pointed at the battlefield" is often as dramatic as its gets, those shots of cannon should be limited [I have included just a half-dozen or so among 50 sites]. Following the illustrated list are my recommendations for specific books on each site, or references to media — movies or animated Internet resources — that help one understand the battles or site. |

MORE PERSONAL COMMENTARY It may seem incongruous, if not downright eccentric, to find the “50 Best Civil War Sites” on this web site, which is otherwise focused on natural history, and primarily birds and birding. It may also seem odd that a person who is a downright tree-hugger should be so interested in a war. I cannot really explain that dichotomy. I don’t wish to participate in any war; I don’t wish to personally engage in re-enactments of battles; nor do I wish to argue politics or history. I just deeply enjoy reading history, and visiting historical sites. I do believe that slavery was the greatest stain on American history, and that John Brown was quite right when he wrote, on the day of his execution, that “"the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. ” I cannot imagine how slavery in the United State would have been abolished — completely, cleanly , and simply — without a catastrophic war. It has taken us a century and more to deal with integration issues, and they are not yet over. But it took this war — in retrospect, a "good war" — to wipe out slavery.

I had read substantial Civil War history before high school and, obviously, I studied more Civil War history while earning a degree in history. It is fair to say that I focused heavily on birding the next 20 years, but regained an interest in Civil War history in the 1990s. No doubt Ken Burns’ (1990) PBS series The Civil War was a part of this reawakening, and I have enjoyed watching it multiple times. What I found particularly fascinating was the way in which the history of this period was interpreted by the 1990s, and how different that interpretation had been in the 1960s. It seemed like “everything that I’d ever learned about the Civil War” when I was young was, in fact, wrong.

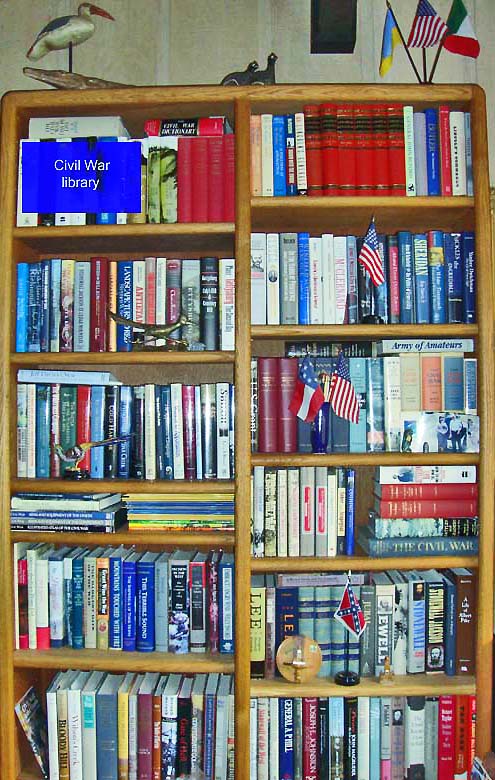

Overlooked entirely during the century of re-writing history was the fact that human slavery in America was the underlying cause of the War, and had been remedied by the War. Succeeded generations of Northerners were willing to go along with this Southern rewrite of history as the economic prosperity became the focus, or because of the lingering effects of racism (which still exists today), or both. But the civil rights and human rights movements of the 1960s-1970s changed historians clichéd views about the past, and new researchers delved into long-forgotten memoirs and letters. An exceptional new set of historians were writing Civil War histories and biographies in the 1980s & 1990s and into the 21st century. I find it all fascinating. Perhaps the single most important book to affect me in this transition was William Garrett Piston's (1987) Lee's Tarnished Lieutenant: James Longstreet and His Place in Southern History. If there is only one book to read on the topic of Civil War re-evaluation, read this one. I have been building a Civil War library over the past couple decades, haunting used book stores for bargains, trading in books that don’t meet my needs, and vaguely keeping track of new literature as it is published. My Civil War interests focuses on battles and campaigns; the tactics and strategies of generals; the politics of leadership, both civilian and within the military, and how that influenced history; and the personalities of the major players on both sides. I am also interested in how geography influenced events, as well as tactics and heroics and luck, and visiting the sites of battles brings an understanding of that element as nothing read in books can do. In general, I am less interested in the lifestyles of the common soldier, nor the details of Civil War weaponry or medicine, nor the economics of mid-19th century America. I have, of course, read a fair bit on all those topics to understand the War, but I don’t collect many books on those topics. My book collection is of battle or campaign histories; important historical overviews; or focused biographies. In choosing which books to buy or keep, I want books that are fair-minded and not tainted with the whiff of hagiography; that are well-researched and preferably based on substantial original research; and that are by professional historians or serious amateurs who are recognized in their field. In general, I find that most Civil War histories or biographies written before the late 1970s tend to be infused with “lost cause-ism” or over-simplification, and these defects annoy me. I have overlooked some degree of these deficiencies in buying and keeping some of the so-called “great works” on the Civil War [e.g., Douglas S. Freeman (1942-1946) Lee's Lieutenants: a Study in Command, 4 vols.] but mostly I prefer newer works. Many of the really good books have come out only within the last couple of decades, yet, of course, these rely heavily on original documents. |

Some quick opinions on Civil War histories:

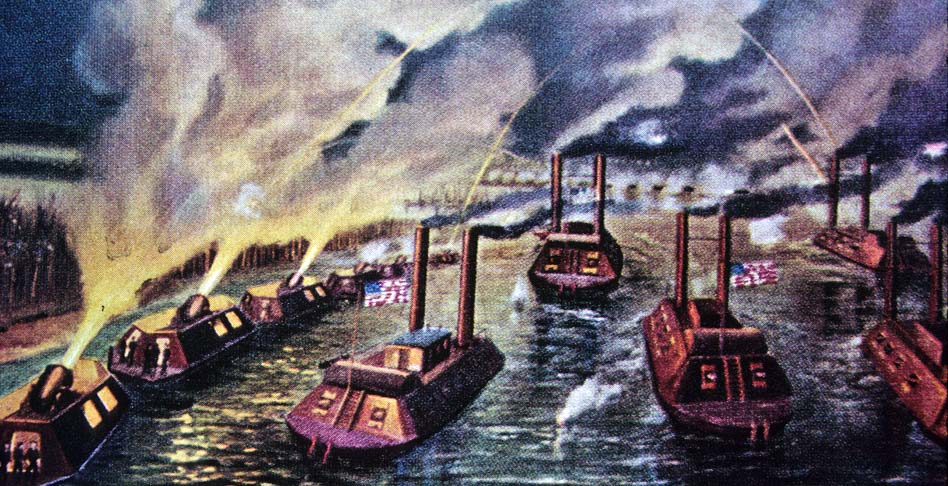

The Civil War also inspired a century's worth of interesting art. I have long admired evocative pieces -- from this contemporary view of Union gunboats attacking Island No. 10 on 13 March 1862 (below) to the modern works of Don Troiani, Mort Künstler, or John Paul Strain. Wonderful artworks are featured in many Civil War museums [for example, ask at the Winchester visitor center's for directions to the research center whose hallways are lined with fine Civil War art] and other reproductions appear on battlefield signs. In all cases, they add dramatically to our understanding and appreciation of this period in American history. Acknowledgments: I am indebted to my wife Rita Carratello for her company and interest in visiting these sites. Rita and Bruce Deuel read an earlier version of these pages, and suggested many helpful improvements, for which I am very grateful. Civil War historians who encouraged my amateur interest include Edwin Bearss, Chris Calkins, and William Garrett Piston. -- Don Roberson [comments welcome] |

|

The cities of Atlanta, Nashville, and Corinth have grown and covered over almost all the important locales critical to those Civil War battles. Urbanization of smaller cities -- Franklin and Murfreesboro, Tennessee, come to mind [photo, right: view from entrance to Stones River NB at Murfreesboro] -- have so encroached that the battlefields are now considered endangered. Only 5 acres were saved of the 5000 acre battlefield at Ox Hill/Chantilly. The Tennessee Valley Authority drowned Ft. Henry when they dammed the Tennessee River. Island No. 10, so critical in 1862, no longer exists -- the Mississippi River swallowed it whole long ago. The Atlantic Ocean washed away Battery Wagner, South Carolina, and a chunk of Ft. Fisher, North Carolina.

The cities of Atlanta, Nashville, and Corinth have grown and covered over almost all the important locales critical to those Civil War battles. Urbanization of smaller cities -- Franklin and Murfreesboro, Tennessee, come to mind [photo, right: view from entrance to Stones River NB at Murfreesboro] -- have so encroached that the battlefields are now considered endangered. Only 5 acres were saved of the 5000 acre battlefield at Ox Hill/Chantilly. The Tennessee Valley Authority drowned Ft. Henry when they dammed the Tennessee River. Island No. 10, so critical in 1862, no longer exists -- the Mississippi River swallowed it whole long ago. The Atlantic Ocean washed away Battery Wagner, South Carolina, and a chunk of Ft. Fisher, North Carolina. The National Park Service operates at least 35 sites (not counting minor Civil War connections within three National Parks), which host at least parts of 64 battlefields or other significant war-related sites

The National Park Service operates at least 35 sites (not counting minor Civil War connections within three National Parks), which host at least parts of 64 battlefields or other significant war-related sites  It is true enough that I am first-and-foremost a birder, but that does not mean I’m not interested in a host of other things, and these include mammals, reptiles & amphibians, dragonflies, current events, politics, movies, theatre, music, sports (esp. my San Francisco Giants & 49ers), wine, art, and history. Indeed, my college degrees are in History and Political Science. I was introduced to the Civil War by my father during the Centennial celebrations 1961-1965. When our family undertook a cross-country trip, pulling a trailer and staying in campgrounds in 1967, my dad permitting me to help pick the route and the sites to be seen. Among my high priority choices at that time -- as a 15-year-old -- were the battlefields at Shiloh, Stones River, Antietam, Gettysburg, and in the Virginia corridor between Washington, D.C. and Richmond.

It is true enough that I am first-and-foremost a birder, but that does not mean I’m not interested in a host of other things, and these include mammals, reptiles & amphibians, dragonflies, current events, politics, movies, theatre, music, sports (esp. my San Francisco Giants & 49ers), wine, art, and history. Indeed, my college degrees are in History and Political Science. I was introduced to the Civil War by my father during the Centennial celebrations 1961-1965. When our family undertook a cross-country trip, pulling a trailer and staying in campgrounds in 1967, my dad permitting me to help pick the route and the sites to be seen. Among my high priority choices at that time -- as a 15-year-old -- were the battlefields at Shiloh, Stones River, Antietam, Gettysburg, and in the Virginia corridor between Washington, D.C. and Richmond.  For a century after the Civil War, the South promoted the myth of the Lost Cause. It postulates that the Confederacy was doomed from the start in its struggle for independence by the superior might of the Union, yet it fought heroically for the cause of states rights. Within the myth Lee and Jackson are venerated as great generals, while Union generals and heroism is dismissed. Grant, for example, was portrayed as a drunk or a butcher. Southern generals who, after the War, supported Reconstruction, were blamed for as well (Longstreet in particular, criticized for being “slow” to follow Lee’s orders). This attempt to rewrite history was intentional and effective. There is a wonderful book of essays on this century-long effort to romanticize the South and to misrepresent the War's true origins: Gary W. Gallagher & Alan T. Nolan's (2000) The Myth of the Los Cause and Civil War History.

For a century after the Civil War, the South promoted the myth of the Lost Cause. It postulates that the Confederacy was doomed from the start in its struggle for independence by the superior might of the Union, yet it fought heroically for the cause of states rights. Within the myth Lee and Jackson are venerated as great generals, while Union generals and heroism is dismissed. Grant, for example, was portrayed as a drunk or a butcher. Southern generals who, after the War, supported Reconstruction, were blamed for as well (Longstreet in particular, criticized for being “slow” to follow Lee’s orders). This attempt to rewrite history was intentional and effective. There is a wonderful book of essays on this century-long effort to romanticize the South and to misrepresent the War's true origins: Gary W. Gallagher & Alan T. Nolan's (2000) The Myth of the Los Cause and Civil War History.