A PHOTO DISCUSSION ON NUTTING'S

FLYCATCHER IDENTIFICATION:

Part 1: WING PATTERN

text © 2003 Don Roberson

all photographs are copyrighted © 2003

by the photographers cited; used here with permission

Under the topic of "Wing Pattern," we will consider the patterns

formed by the colorful edges to the remiges, and then consider primary

projection.

WING PANELS: This topic was introduced on the opening

page of this set. The remiges (flight feathers) were divided into three

elements, or panels:

-

primary edges

-

outer secondary edges

-

tertials and inner secondary edges

Let us first look at Ash-throated Flycatcher. This is a photo taken on

or near the breeding grounds in late spring (the slide is imprinted "May

1976"; photo © J. Van Remsen) at Ft. Piute, San Bernardino Co., California.

Thus the edges of the remiges are somewhat worn, but their color pattern

is still quite obvious.

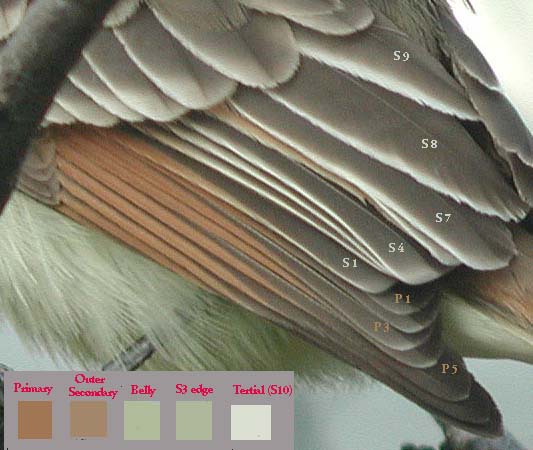

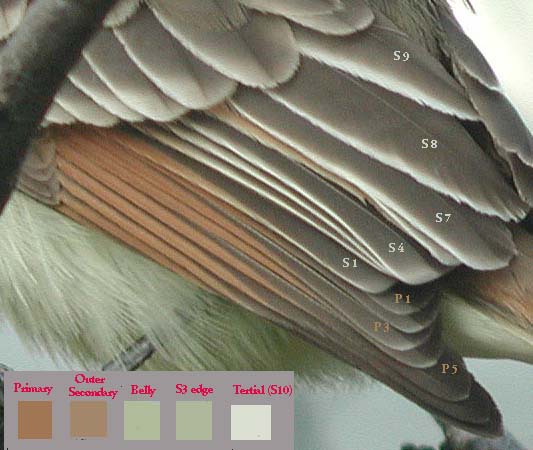

We can also examine the wing in more detail to examine the numbering system

used in the banding literature (e.g., Pyle 1997) and consider other points.

The numbering system is designed to match the way in which most birds conduct

their molt. The primaries ("P" in shorthand) are molted from the inner

ones to the outer ones, and are therefore numbered from the inside out.

The secondaries ("S" in shorthand) are replaced from the outermost to the

innermost, and are therefore numbered from the outside in. Although landbirds

do not have "true" tertials like some waterfowl or other groups, birders

and banders have generally agreed to call the innermost three secondaries

(thus S7, S8, S9) the tertials:

We can also examine the wing in more detail to examine the numbering system

used in the banding literature (e.g., Pyle 1997) and consider other points.

The numbering system is designed to match the way in which most birds conduct

their molt. The primaries ("P" in shorthand) are molted from the inner

ones to the outer ones, and are therefore numbered from the inside out.

The secondaries ("S" in shorthand) are replaced from the outermost to the

innermost, and are therefore numbered from the outside in. Although landbirds

do not have "true" tertials like some waterfowl or other groups, birders

and banders have generally agreed to call the innermost three secondaries

(thus S7, S8, S9) the tertials:

| I have attempted to number the remiges. I believe that the secondaries

are correctly numbered, but am less sure about the primaries. You see there

is a gap between what I have numbered P3 and P5. It is possible that P4

is missing due to an accident. It is also possible that what I have labeled

as "P5" is actually P4, and, if so, then all the numbers larger than that

are off by one. It is also possible that the feather labeled P10 is actually

the base of P9, and that P10 is entirely hidden below it. P10 — the outermost

primary — is considerably shorter than adjacent primaries.

For fun, I used the PhotoShop color picker for the colors of the numbers.

The P numbers are matched to the color of the edges of the inner primaries.

The S numbers are matched to the color of the tertial edges. Recalling

the "three panel" system described on the introductory page, you can see

that the pattern is "red-white-white" (i.e., rufous edges to primaries,

white edges to S1-S4, and white edges to S5-S9).

Note yet something else: the edges of the outer primaries (e.g., P6-P8)

look more orange and less deep rufous than the inner primaries (e.g., P1-P3).

I think it is fair to attribute this to sun bleaching. Recall this is a

May photo so the edges have been subjected to sun for perhaps 8-10 months.

When the bird is perched (which is most of the time) only the outer primary

edges are in the sun, so they bleach while the inner ones do not. Even

with that amount of sun bleaching, the essentially rufous character of

the color is still there. As the inner ones did not bleach, the stark contrast

between deep rufous on P1 — even in an old feather — and the white edging

to S1, is quite obvious. |

|

Let us now look at the two Nutting's we are using for reference. Below

left is the southern California bird in a fine shot © Larry Sansone;

to the right is another Ed Harper shot of the Arizona bird.

Undoubtedly the most important paper on the Nutting's vs. Ash-throated

problem is Lanyon (1961). He reviewed 485 specimens of Ash-throated, and

229 of Nutting's, all adults in fresh plumage (Sep-Feb) to develop his

plumage keys. In my view, this research is much more important than anecdotal

evidence reported by some about their experiences with a handful (and sometimes

just one or two) birds. As to the wing-panel, Lanyon wrote that Ash-throated

"M. cinerascens has the fringed leading edges of the secondaries

whiter than those of M nuttingi. In M. cinerascens, the deep

rufous edging characteristic of the primaries is never present on

the secondaries (the first secondary may be edged with a very pale rufous)

and the remaining secondaries and tertials are edged with white or grayish

white. In M. nuttingi the deep rufous edging of the primaries

is always present on at least the first secondary and then

fades to a pale rufous or brownish white on the remaining secondaries —

only the tertials are white or grayish white" [emphasis added].

There is one very important caveat: "In using this character, one must

be careful to recognize those specimens of M. cinerascens that are

still

in the process of postjuvenal molt, for the secondaries of the juvenal

plumage of that species are edged with pale rufous and would be confusingly

similar to the condition found in adult M. nuttingi. It is not uncommon

to find specimens collected as late as November and December that still

retain one or two of the juvenal secondaries.... The character can be used

in these specimens, however, for the last secondaries to be replaced are

the inner ones (next to the tertials). Consequently, in molting M. cinerascens,

those

secondaries located adjacent to the primaries will have the white edges

typical of adults" (emphasis added).

| Having learned how to separate the two species on wing-panel characters

— if we can correctly age the bird to exclude juvenal outer secondaries

— let's look at the Santa Cruz bird using a portion of a great Kevin McKereghan

digital photo through a fine scope. To the right is that portion of the

photo and then the same shot with the remiges numbered: |

|

| There are many interesting points here. S1 through S4 have fresh clean

edges while S5 (not numbered but just above S4) is obviously worn, and

it is a pale rufous or orange color. This is what Pyle (1997) terms "molt

limits;" S5 is a worn and retained juvenal feather, and ages this bird

as a bird in first-basic plumage, having been born in summer 2002. It was

skipped during the molt as the remaining inner secondaries are fresh. Because

the juvenal secondaries are replaced from the outside in, S1 through S4

are fresh basic secondaries having the characteristics of adult feathers.

I see that S1, the outermost secondary, is very broadly edged rufous, and

that the color is almost identical to the deep rufous of the primary edges.

S 2 is paler, but still has much orange at its base, and then S3 and S4

are paler still. |

|

Some who have reviewed this photo on Joe Morlan's web site state that the

color of the edges of S2 (excluded the orangey base) through S4 is whitish,

and thus better for Ash-throated. This is an opinion different from most

who studied this feature in the field, often with high-powered scopes.

Most of us saw a pale-yellow (called "cream" by some people) color to these

edges. So I have also done another test on this last photo. Using the PhotoShop

color picker at the half-way point of individual feathers and in the center

of the colorful edge, I have filled five boxes with the colors that the

computer found there. The left hand box is the color found in the edge

of P1, the innermost primary. The next box has the color found mid-way

out on S1, the outer secondary. You can judge for yourself whether this

color is a deep rufous color similar to the primaries — as Lanyon (1961)

says is diagnostic of Nutting's — or a whitish or, at most, "very pale

rufous," which is diagnostic of Ash-throated (now that we know these are

not juvenal feathers). The center box is the color of the belly as shown

in this photograph. [Incidentally, for fun I also used that color to number

the secondaries so you could see how it looked next to the dark color of

the rest of the feather.] The box after that is the color of the edge of

S3. You can judge for yourself whether that color is similar to the color

of the belly. If it is, and you call the belly "yellow," then, a priori,

the edge of S3 is also in the "yellow" category. The final box is filled

with the color of the edge of S10, the uppermost tertial. This is a color

I call "cream" but whatever the exact language, it is clearly in the white

to whitish category.

I have four more thoughts for you to consider about the colors of the

remige edges:

-

Some have stated that they expect the secondaries of Nutting's Flycatcher

to be rufous (like the primaries) rather than orangey or yellow. This is

contrary to Lanyon's study. However, for what its worth, Howell & Webb

(1994) state that southern populations of Nutting's are more richly colored

on the wing panel and belly than northern populations. The only specimen

collected in the U.S. was of the northern subspecies, M. n. inquietus

(Dickerman & Phillips 1953). It is possible that those who rely on

field experience with the southern nominate race (s. Mexico to Costa Rica)

may be comparing apples to oranges (pun intended).

-

Whether or not you agree that the color of S3 (and most of S2 and S4) is

the color of the belly, i.e., in the "yellow" category, it does look less

yellow than on the photos of the Arizona and southern California birds,

where I "see" actual lemon-yellow without the aid of computerized technology.

One possible reason is that, however crisp and wonderful this digital photo

may be, is has washed out the yellows. We can tell that because the belly

is less yellow than on most of the other photos of this bird and much paler

than described in the field. I think it is possible that digital photography

may be great for showing fine details with clarity, but may be less accurate

in capturing exact colors. I will show another possible example of this

on the Plumage page when we compare digital photos — both taken with digital

cameras held up to scopes — of the head colors. McKereghan's set-up (an

Olympus 3030 digital camera with a Leica APO 77 scope with 30-60X eyepiece"

is different than Tom Grey's set up (an Olympus 550 digital camera with

a Nikon Fieldscope 60 ED). I think the Leica gives a "cool" cast to the

photos while the Nikon brings a "warm" cast, even accounting for differences

in natural lighting (or maybe those differences are inherent in the cameras?).

There are some who have conducted an entire review off this single McKereghan

photo but, excellent as it is, it may be unwise to limit one's opinion

to one photo.

-

The other thought is derived from Lanyon's (1961) statement about the value

of the secondary pattern: "The second character [wing panel] is the most

transitory and is of no use in specimens taken after November." Why did

he say this? Obviously, it was because the characters were "transitory"

or, more directly. subject to fading. You will recall that in studying

the Ash-throated Flycatcher (above), we found that the depth of the rufous

color of the outermost primaries had faded somewhat by May. Thus when Lanyon

speaks of the secondary pattern as "the deep rufous edging of the primaries

is always present on at least the first secondary and then fades to a pale

rufous or brownish white on the remaining secondaries — only the tertials

are white or grayish white," we would expect that color to fade as the

months after November go by. All the photos on this page (except Ash-throated)

are from early January, just a month to six weeks after the end of November.

So only partial fading has occurred. I would expect the "pale rufous" to

fade to yellow within a couple months, and the "brownish-white" to fade

to even a paler whitish color. If this hypothesis is correct, the "yellow

mid-panel" that I have discussed so much up to this point is also transitory,

and may be only a useful feature from, say, December through February.

-

Finally, the nice yellow "mid-panel" pattern shown by the Arizona and southern

California birds are on birds we have aged as adults. Perhaps first-winter

Myiarchus

average paler-edged secondaries than adults. It is not unusual for first-year

birds to average paler than adults in some features. I am unaware of any

literature than addresses this point.

PRIMARY PROJECTION

Although

it is not addressed in the literature, it was suggested during the discussions

of the Arizona bird that Nutting's had a shorter primary projection (the

number of primaries sticking out beyond the longest tertial on a closed

wing) than Ash-throated Flycatcher. It was proposed that Nutting's typically

shows only 3 primaries so projecting, while Ash-throated has four or more.

Pyle (1997) notes that Ash-throated has a more pointed (=longer looking)

less rounded wing than Nutting's. On this April photo of an Ash-throated

from Morongo Valley (right; © D. Roberson), we can't count the primaries

but we can get a bit of the "long-winged" feeling that such a wing shape

would present.

Although

it is not addressed in the literature, it was suggested during the discussions

of the Arizona bird that Nutting's had a shorter primary projection (the

number of primaries sticking out beyond the longest tertial on a closed

wing) than Ash-throated Flycatcher. It was proposed that Nutting's typically

shows only 3 primaries so projecting, while Ash-throated has four or more.

Pyle (1997) notes that Ash-throated has a more pointed (=longer looking)

less rounded wing than Nutting's. On this April photo of an Ash-throated

from Morongo Valley (right; © D. Roberson), we can't count the primaries

but we can get a bit of the "long-winged" feeling that such a wing shape

would present.

Go back to the photo at the top of this page and in your "mind's eye"

fold up the wing. S8 is the longest tertial, and I can see that obviously

that the tips of four primaries, numbers P5 through P8 on this page (whose

numbering may be off by one, as discussed above), would well extend beyond

S8 (and any other secondary), and possibly one or two more tips would also

stick out. On Larry Sansone's very nice shot of the Orange County bird,

it is apparent that only 3 primary tips are projecting. We can't see details

of the Arizona bird, but the primary projection is short, and is consistent

with the Orange County bird's shape.

On the Santa Cruz bird, using the photo above and folding it up, it

looks to me that only three primary tips (numbered 5, 6, and 7 in the photo)

would extend beyond the longest tertial (S8). Assuming the numbers are

correct, P8 — usually the longest primary in many flycatchers — is hidden

under P7 and must be essentially the same length, with P9 somewhat shorter.

This would be a rounded wing and is consistent with Pyle's (1997) details

on Nutting's, who explains that P9 is just barely longer than P5 (by 1-3

mm) in Nutting's, but that P9 is quite a bit longer (3-7 mm) than P5 in

Ash-throated. If you look at the Ash-throated at the top, and if the numbering

is correct, P9 does look a fair bit longer than P5, consistent with a 3-7mm

difference. However, since we can't actually see all the outer primaries,

these points are conjecture. You may judge what weight to place on them.

The other pages in this project are:

LITERATURE CITED:

-

Bowers, R.K., Jr., and J.B. Dunning, Jr. 1987. Nutting's Flycatcher (Myiarchus

nuttingi) from Arizona. Amer. Birds 41:5-10.

-

Cardiff, S.W., and D.L. Dittmann. 2000. Brown-crested Flycatcher (Myiarchus

tyrannulus) in The Birds of North America, No. 496 (A. Poole

and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

-

Cardiff, S.W., and D.L. Dittmann. 2002. Ash-throated Flycatcher (Myiarchus

cinerascens) in The Birds of North America, No. 664 (A. Poole

and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

-

Devillers, P. 1971. The alleged occurrence of Nutting's Flycatcher in Baja

California. Calif. Birds 2:140.

-

Dickerman, R.W., and A.R. Phillips. 1953. First United States record of

Myiarchus nuttingi. Condor 55:101-102.

-

Dittmann, D.L., and S.W. Cardiff. 2000. Let's take another look: Myiarchus

flycatchers. LOS News 193:3-10. Louisiana Ornithol. Society, Baton Rouge.

-

Howell, S.N.G., and S. Webb. 1994. Field identification of Myiarchus

flycatchers in Mexico. Cotinga 2:20-25.

-

Howell, S.N.G., and S. Webb. 1995. A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and northern

Central America. Oxford Univ. Press, New York.

-

Lanyon, W.E. 1961. Specific limits and distribution of Ash-throated and

Nutting flycatchers. Condor 63:421-449.

-

Lanyon, W.E. 1997. Great Crested Flycatcher (Myiarchus crinitus)

in

The Birds of North America, No. 300 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds

of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

-

Murphy, W.L. 1982. The Ash-throated Flycatcher in the East: an overview.

Amer. Birds 36:241-247.

-

National Geographic Society. 1999. Field Guide to the Birds of North America,

3rd ed. Nat. Geogr. Soc., Washington, D.C.

-

Phillips, A.R., and W.E. Lanyon. 1970. Additional notes on the flycatchers

of eastern North America. Bird-Banding 41:190-197.

-

Pyle, P. 1997. Identification Guide to North American Birds, Part I: Columbidae

to Ploceidae. Slate Creek Press, Bolinas, CA.

-

Zimmerman, D.A. 1978. A probable Nutting's Flycatcher in southwestern New

Mexico. West. Birds 9:135-136.

TOP

GO TO MONTEREY

COUNTY PAGE

GO TO HOME PAGE

GO TO

IDENTIFICATION PAGE

GO TO BIRDING THE

WORLD PAGE

GO TO BIRD FAMILIES

OF THE WORLD

Page created 23-24 Jan 2003

Although

it is not addressed in the literature, it was suggested during the discussions

of the Arizona bird that Nutting's had a shorter primary projection (the

number of primaries sticking out beyond the longest tertial on a closed

wing) than Ash-throated Flycatcher. It was proposed that Nutting's typically

shows only 3 primaries so projecting, while Ash-throated has four or more.

Pyle (1997) notes that Ash-throated has a more pointed (=longer looking)

less rounded wing than Nutting's. On this April photo of an Ash-throated

from Morongo Valley (right; © D. Roberson), we can't count the primaries

but we can get a bit of the "long-winged" feeling that such a wing shape

would present.

Although

it is not addressed in the literature, it was suggested during the discussions

of the Arizona bird that Nutting's had a shorter primary projection (the

number of primaries sticking out beyond the longest tertial on a closed

wing) than Ash-throated Flycatcher. It was proposed that Nutting's typically

shows only 3 primaries so projecting, while Ash-throated has four or more.

Pyle (1997) notes that Ash-throated has a more pointed (=longer looking)

less rounded wing than Nutting's. On this April photo of an Ash-throated

from Morongo Valley (right; © D. Roberson), we can't count the primaries

but we can get a bit of the "long-winged" feeling that such a wing shape

would present.